©Laurence Svirchev

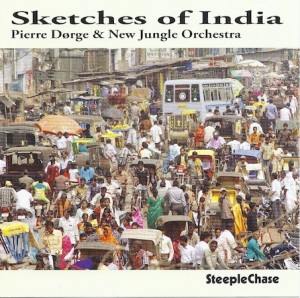

Sketches of India is a musical travelogue that shimmers with mosaical scenes of intense beauty, contemplative emotion, and spectral landscapes. Dørge’s approach to this CD is to integrate and differentiate the forms of Indian music with the jazz forms he is intimate with. Having traveled for decades to all the human-occupied continents, Dørge and the New Jungle Orchestra are no strangers to adsorbing musical indigenous forms and then expanding on them. This can be a tricky process for people enamored with musics outside their normal ken, but Dørge and company have the curiosity, chops, and musical integrity to follow the well-honed instincts that have kept this band alive since its foundation in 1980. Some compositions, for example “Papanasum Mood,” contain overt Indian forms, in this case Carnatic music, and then resolve themselves into jazz forms. Pianist Irene Becker’s composition, “Indian Night Sky”, makes no attempt to delve into Indian forms, but “Another Raga” is clearly based on Indian scales.

Sketches of India is a musical travelogue that shimmers with mosaical scenes of intense beauty, contemplative emotion, and spectral landscapes. Dørge’s approach to this CD is to integrate and differentiate the forms of Indian music with the jazz forms he is intimate with. Having traveled for decades to all the human-occupied continents, Dørge and the New Jungle Orchestra are no strangers to adsorbing musical indigenous forms and then expanding on them. This can be a tricky process for people enamored with musics outside their normal ken, but Dørge and company have the curiosity, chops, and musical integrity to follow the well-honed instincts that have kept this band alive since its foundation in 1980. Some compositions, for example “Papanasum Mood,” contain overt Indian forms, in this case Carnatic music, and then resolve themselves into jazz forms. Pianist Irene Becker’s composition, “Indian Night Sky”, makes no attempt to delve into Indian forms, but “Another Raga” is clearly based on Indian scales.

The first composition, “In the Tiger Cave”, was inspired by a visit to a cave adorned with huge sculptures of the sacred carnivorous beast. The introduction is a peaceful piano solo from Irene Becker and she is gradually joined, first by the lower-register instruments, then progressively by the rest of the ensemble. Within the repeating melodic line there is a feeling of tenderness filled with muted and subtle colors. There is another emotion at play In this music. The slow pacing and the very deliberate voicings of the brass and reeds lend a reverential quality to the composition. Anyone who had been in the presence of a real tiger knows how the power of this beast provokes awe. What I heard in the music was a slight shiver of fear as the musicians viewed stone forms of the ferocious animal.

“Dawn by the Sea” is divided into three sections. That signature of Indian music, the drone, opens the composition. Morten Carlsen, playing the dark-sounding taragot, solos over the drone completely into the second section in which variations on the melody are incrementally developed. The third section is essentially a trumpet solo by Gunnar Halle. Dividing the song into three sections, however, is a simplistic illustration of this complex composition. What is really happening in the music is a steady march of progression, densification, and development, a bit martial in cadence as if the world were ordered by the increasing brilliance of the rising sun. The music is marked by the changes in color and temperature as the light and warmth of the rising sun reflect off the ocean, sand, and the sails of fishermen’s boats.

To sit on a shoreline and watch the changing of the guard, what Homer referred to as the goddess Eos opening the gates of heaven for the sun to rise, is to witness the transition between the depths of the universe and the first illuminations of our splendid world. The darkness and tension of the drone and taragot sound out this mysterious phenomena. In my listening, the drone provoked a wonder: does the drone, normally played by a shruti-box, come from Becker’s synthesizer or is that Dørge on the guitar? In the early years of the Ellington band, many listeners, critics and professional musicians alike could not figure out, based on recordings, how the music was voiced. It took the visual evidence of listening at concerts to understand that Ellington’s voicings were genius, that they made an ensemble sound that transcended what every other composer of the time was doing. The New Jungle Orchestra has that same fifth element, it is called ‘quintessence’, that makes the band other-worldly.

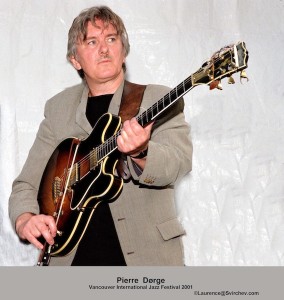

Quintessence is also at work on “Papanasam Mood. Like “Dawn by the Sea”, the composition starts at low pitch, an arco bass line as the “alap” (improvisation as a prologue to the formal expression of a raga). The synthesizer and horns enter at low pitch, subtle, layered deep in the background, and powerful. Anders Banke’s clarinet and the rest of the horns alternate on the melody. Just when the time is ripe to launch a charge of energy, the music fades and Dørge begins a solo in the style of an Indian stringed instrument, percussive plectrum attack plentiful on the strings. During Kenneth Angerholm’s trombone solo, Dørge uses a variety of techniques, straight western-style jazz, and slide.

Quintessence is also at work on “Papanasam Mood. Like “Dawn by the Sea”, the composition starts at low pitch, an arco bass line as the “alap” (improvisation as a prologue to the formal expression of a raga). The synthesizer and horns enter at low pitch, subtle, layered deep in the background, and powerful. Anders Banke’s clarinet and the rest of the horns alternate on the melody. Just when the time is ripe to launch a charge of energy, the music fades and Dørge begins a solo in the style of an Indian stringed instrument, percussive plectrum attack plentiful on the strings. During Kenneth Angerholm’s trombone solo, Dørge uses a variety of techniques, straight western-style jazz, and slide.

The Indian shruti box is not listed as an instrument on the CD. After puzzling my way through the opening ingredients of “Dawn by the Sea”, and finding no satisfactory answer about how the drone was made, I asked Pierre Dørge to explain. He said via email that he used “open string tuning played with my small violin bow.” He embellished his thoughts by saying that he plays the string sound of the electric guitar without electronic manipulation. “When I meet new string instruments around the world, I study them. It takes a whole life to learn the instruments. I try to transfer these instrument sounds to my way of playing guitar. Sometimes I imitate the sound and sometimes try to imitate the instrumental technique, like the way the strings are attacked with the plectrum in Japanese and Chinese music.”

Dørge’s compositions and the musicianship of this long-standing band place it in the supreme category of contemporary creative music. Paradoxically, they are not well known in the North American jazz world. On the other hand, North American is not the only continent that hungers after creative jazz music. In Sketches of India, I find a profound respect for the traditions of India, and a clairvoyant insight into the complexities of Indian music. It feels like the musicians actually brought home substantial quantities of Indian soul in their hearts, breaths, and fingertips.

Sketches of India is published by Steeple Chase SCCD 31728