François Houle has always been an artist who works with a surgeon’s precision but equally with an expansive musical palate. Recoder consists of seven through-composed works by Houle, the co-musicians being Gerry Hemingway, Mark Helias, and Gordon Grdina, and a surprise organizational quirk in the form of eight completely improvised duets. The opening improvisation is “Prelude” and the CD ends with another improvisation, “Postlude.” In between each long-form composition is an interlude, a clever, adroit, agile, and a supremely effective way to differentiate the highly structured lengthy compositions. A good thing, for each of the long compositions are heavy-weights. Differentiating them with the counterweight of duets gives the listener not necessarily lightness, but a breathing spell. This kind of organizational device may not be novel, but the way Houle designed the device is. All of the interludes are clarinet duets between Houle and Helias, whose working instrument is the bass. Helias on clarinet, who’d a thunk.

François Houle has always been an artist who works with a surgeon’s precision but equally with an expansive musical palate. Recoder consists of seven through-composed works by Houle, the co-musicians being Gerry Hemingway, Mark Helias, and Gordon Grdina, and a surprise organizational quirk in the form of eight completely improvised duets. The opening improvisation is “Prelude” and the CD ends with another improvisation, “Postlude.” In between each long-form composition is an interlude, a clever, adroit, agile, and a supremely effective way to differentiate the highly structured lengthy compositions. A good thing, for each of the long compositions are heavy-weights. Differentiating them with the counterweight of duets gives the listener not necessarily lightness, but a breathing spell. This kind of organizational device may not be novel, but the way Houle designed the device is. All of the interludes are clarinet duets between Houle and Helias, whose working instrument is the bass. Helias on clarinet, who’d a thunk.

It is wise to not thunk too much because Gordon Grdina and Gerry Hemingway are also great composers, interpreters, formidable thinkers, and leaders in their own right. If a listener never considered that Helias could deliver on the clarinet then this CD should be enough to convince listeners not to limit our own imaginations. Neither did the musicians on this recording. What follows in this essay is an examination of Houle the composer and three of the compositions, “Big Time Felter,” and “Bowen,” and “Morning Song 1 (for Ted Byrne).”

Big Time Felter

In the transitory interludes there is gentleness, an easement which serves to enhance the muscularity of the longer full quartet compositions. Consider the “Big Time Felter,” a reference to the oldest textile art, the matting, condensing, and pressing fibers of animal wool or fur together. Felting involves the natural hands-on process of commingling and compressing a mass of entangled interwoven stuff, maybe from different animal sources, into an integrated whole. The inspiration here was young woman learning this slow and meticulous process. Expressed in this music, it is an intense and high velocity experience by musicians who long ago learned the elixirs of musical quantum entanglement.

One way to felt musically is to counterpoint and tempo-shift within the song organism. “Big Time Felter,” is marked by Grdina’s opening statement, an improvisation on the melody, Helias in an up-front pulse. Then Houle enters, stating the melody with Grdina, the two expressing it in rapid-fire improvised counterpoint with Grdina in slight delay from Houle’s lead. Closely-linked tandem improvisation, two statements in one, in fact a characteristic Houle-Grdina musical pattern found throughout the CD. Bam! comes the drop in tempo for Helias’ arco solo, a transition into deep pizzicato ending on a glissando, all accompanied by Hemingway’s cymbal splashes, high hat double-takes, and a sort of tattoo providing coloration.

Hemingway often refers to his instrument as “tubs,” that gloriously descriptive term from the antiquity of jazz. He ends this section (in time with Helias’ glissando, these two have been playing together for a very long time) with a couple of beautifully controlled soft bombs on the bass drum, and it is back to Grdina and Houle stretching out in tandem. All this in a couple of minutes, leading into Houle’s solo and then Grdina’s hard rapid-fire plectrum strokes leaving far more to discover in this densely-woven composition.

Bowen

From the WWII German prisoner of war camp in 1941 called Stalag VIIIA to Bowen Island, British Columbia in 2019 is a long journey in space and time. But not necessarily so, for music is a right-now experience that has the capacity to amplify the space-time continuum. The longtime church organist and composer Olivier Messiaen, drafted and serving as medical corpsman, was captured during the German invasion of France and confined to Stalag VIIIA. Having been helped by a sympathetic German to a pencil and some paper, he composed Quatuor pour la fin du temps (Quartet for the End of Time) for clarinet, cello, violin and piano, performing it for the first time in that Stalag on 15 January 1941. Could the cold and desolation of a prisoner of war camp bound by the seeming invincibility of the Nazi degenerates been the ideal place to imagine the end of time and give birth to a white-hot core composition?

Houle has performed Quatuor pour la fin du temps on multiple occasions and he freely states that his compositon “Bowen” borrows heavily from the sixth movement of the Quatuor, sub-titled “Dance of fury, for the seven trumpets”. Messiaen himself described this section as, “Music of stone, formidable granite sound; irresistible movement of steel, huge blocks of purple rage, icy drunkenness.” Such a description is not the natural state of affairs on Bowen Island, for the island possesses preternatural beauty and a mild climate. The gentle nature of the people who seek solace in this place enhances that beauty. The island is a short ferry ride from the “Big Smoke,” which is how Vancouver was known when it was a polluted pulp and saw mill town. Long after most of the trees and shanties were torn down and the skid roads replaced with pavement and stone buildings, tiny and insignificant Vancouver became a kind of Camelot in which the creative home-town musicians were able to mix in a big way, at least twice a year, with the most imaginative of international musicians. It became a scene which included the Western Front as one of the small venues people like Houle, Hemingway, Helias, and Grdina have played frequently as their careers brought them to international stages.

The vision and organizational force for these developments was a most-genial man with genius ears, a Prince and his Guinevere who convivially hosted musicians with wine, gourmet-cooked food, and for listening a most esoteric collection of LPs a tube amplifier, turntable, and Mission 770 speakers. He was the guy who always came down on the one when he booked concerts for the Vancouver cauldron. Surrounded by music and friends, the hardest work over and a body of work firmly established and proud of it, retirement should have then been the relaxation of lamb stew, of strawberries, sweetened cream, and the sipping of Oban.

Then it wasn’t, the prospectus of joyous tranquility desecrated when along came a dreaded medical diagnosis. But at least he was able to spend the last tenure of life with his Guinevere on Bowen Island, occasioned by lifelong friends who visited to share the last times. For those who know the personalities, that’s one Way to listen to “Bowen.”

The Way also designates another listening pathway: the composition “Bowen” is a kind of Stephen Hawking/Roger Penrose gravitational singularity, a song emotion-laden with the universal. Convivial composition it is not. Deep, dark, mysterious it is, an ominous song that travels to parts of life that cannot be control by the human force of will-power. Its opening theme is dramatic, in-unison plodding almost, the weight of a huge despair chained to the shoulders. Tragedy is unfolding, what Black American church music folks would term ‘a cross to bear.’ Section two is all introspection, the forlorn stare into an unfathomable black-hole abyss, incalculable expectation of the unknown, less than a sliver of improvisation in these two all-unison, through-composed sections.

Consider this: Quatuor pour la fin du temps was written for clarinet, violin, cello, and piano in the desolation of a prisoner of war camp. The François Houle 4 has a different instrumentation, the anomaly being American drum kit, the tubs. Everything has antecedent and one of the composers who paved the way for Messiaen’s music was the German Anton Webern. Messiaen survived the war. Webern survived as well, not by much and then he didn’t. On his CD Songs (2002, BTL) Gerry Hemingway encapsulated the story of Webern’s death, his electronically transformed voice chanting:

“Out for a cigarette, time to die, hushed beauty lost on a soldier’s scared eyes”

It was 15 September 1945 and Webern had taken a smoke break to not disturb a sleeping grandchild. Walking through a doorway at the moment of a black market bust, an American solider who later died of alcoholism fired the three bullets that ended Webern’s life. Webern went from the peaceful moments of a smoke to an unpredictable event, his cortical neurons sundered. There are things we can control, and too many that we cannot.

It is almost eight decades from these tragic events to the present sadness sung in “Bowen.” Passing from generation to generation the music never dies, it is ever-changing with the times. Webern or Messiaen may not have imagined the American drum kit as solo voice in their vocabulary, but imagine the end of time and compose the music for it Messiaen did.

Enter Hemingway and the tubs, his attack as structured as a Roach, Jones, or Morello exposition and just as loose, rolling thunder courtesy of those wide circumference, deep throat cylinders. Hemingway has a slam-a-dam technique of creating, with each component of the kit and with every touch-strike, extreme differentiation of sound. He accomplishes this at any acceleration or deceleration, a universe of space-time curvature. Special attention is warranted to the way Hemingway handles the bass peddle to realize an exceedingly deep, sustained, and long-delaying wave-form (recording engineer Michael Brorby made some marvelous choices here).

In the context of “Bowen” the solo continues the emotional story. The tempo gradually increases reaching denouement at the moment of the re-entry of Houle-Grdina-Helias, with refrains of the sad-slow melody. Hemingway winds down the volume and contra-temp accordingly, this time with some emphasis on the cymbals instead of the skins. The last few strokes of the cymbals could have been a perfect-world peaceful ending to “Bowen.”

Houle chose differently. In section four the composition goes back to the essences of the melody, arises in volume and intensity until on a downstroke from Grdina, the ensemble explodes the music into a electro-magnetic current of magma, black hole density, purple rage not the end of time, but time transformed.

I’ve Been Playing Clarinet for over 50 Years Now

Houle mentioned recently, “I’ve been playing clarinet for over 50 years now.” He is most significantly known for his chops as an instrumentalist and performer, with multiple recordings in context ranging from jazz, contemporary classical, chamber music, and the exceedingly difficult Persian forms (often with Gordon Grdina). When he enters the stage Houle doesn’t ease into the music, his batter-box stance and power-swing is designed to hit grand slams.

Almost from day one he has been musical transubstantiator, the calibre of a Steve Lacy, a comparison that is no stretch. As a young musician trying to find his own path after his Masters studies at Yale, Houle found himself in Paris France studying ancient instruments. It was in Paris that Houle heard the Lacy-Gil Evans album Paris Blues, and it became a divining insight. He travelled back to Canada, leaving his home city near Montréal and found himself in Vancouver. It was an intuitive move, for Vancouver’s long obscure but vibrant improvising scene was just breaking into international recognition, much of that due to Ken Pickering’s programming at the Vancouver International Jazz Festival and the Time Flies series. The Festival at that time was also sponsoring year-round events that brought together leading and new improvisors from around the world, resulting in the sharing of musical DNA.

This terrain led Houle into accelerated contact with the best. There were local collaborations with the newer generations of creative musicians: Tony Wilson, Ron Samworth, Coat Cooke, Kate Hammett-Vaughn, Peggy Lee, Clyde Reed, Dylan van der Schyff. The natural next step was the international collaborations, such as with Marilynn Crispell on Any Terrain Tumultuous. This recording hints at Houle’s compositional inspirations, the mythology of musical heritage (“Marsyas”). There was the natural environment (“For Clayoquot” a wilderness area of west coast British Columbia). His recorded entry into the realm of open improvisation occurred with the 1996 Live at Banlieues Bleues with Joëlle Léandre and Georg Graewe. Then came the first of constantly fruitful collaborations with Benoît Delbecq with the 1997 duo recording Nancali (a sly reference to the composers Nancarrow and Ligeti). An early high-profile critical breakthrough came in 1998 with In the Vernacular, The Music of John Carter, loaded with the heavy artillery of Dave Douglas, Peggy Lee, Dylan van der Schyff and Mark Dresser.

In 1998 came a wrath of nature’s furies, the Québec Ice Storms. Whole towns were frozen into isolation, hydro-electric steel towers became brittle and snapped in the cold winds, ice-laden cables snapped from the swaying weight, roadways to bring relief to the population became impenetrable. In pre-mobile phone communication, telephone lines toppled and locals could not communicate with each other. Houle was on the west-coast of the Canadian, unable to help or even communicate with loved ones across Canada’s vast solitude. Radio and television were the only means to judge the situation. The effect on Houle was profound and he compositionally synthesized this vast national disaster and its recovery into Au Coeur du Litige (The Heart of the Matter) issued in 2000 on the Spool label as two CDs.

If to this point there were hints that Houle was transforming into a major composer: Au Coeur du Litige was the confirmation. In this work, he takes radio recordings from those two weeks, linguistically in the vernacular of Québec French and of English, and transforms them electronically together with the instruments, sometimes as manipulations, others as relatively straight playing, and with poetic voices. The results can be profoundly agitating, as on “Cryogenic Nightmare.” Or when the howling wind has ceased, the peacefulness of “En Attendant la Neige” (Waiting for Snowfall) becomes a settling moment. Au Coeur du Litige encapsulated in large format the elements he had created since coming on the scene: composition using disparate elements of electronics, poetry, radiophonics, improvisation, and the unmanipulated natural sounds of instruments.

A natural followup was 2001’s Cryptology, which took inspiration from Neil Stephenson’s Cyptonomicon, a fictional rendition of the American-British cracking of WWII’s Nazi and Japanese imperial military codes and their business repercussions into the 1990’s. In his liner notes, Houle states, “I began to draw parallels between cryptology and musicology, and soon found myself meditating on the idea of musical notation as code.” The statement is typical Houle, long-form compositional thinking which results in relying on the creative powers of the musicians he gravitates to. Cryptology is a throughly eclectic recording that includes plenty of fuzz-tone guitar, electro-acoustics, melodically beautiful piano, cello, drum, and trumpet work. The cryptology that flows from meditation into complex compositions might be seen in a rear-view mirror as a precondition to Recoder.

Then came a large-ensemble composition, Twenty, dedicated to Steve Lacy. It was commissioned by Ken Pickering for the 20th Anniversary celebration of the Vancouver International Jazz Festival and presented at the Vancouver East Cultural Centre on 2005-06-24. The line-up included Delbecq, Evan Parker, Mark Dresser Although recorded, it was never issued.

The Long View

It is now 15 years since Twenty and Houle’s career has never looked back. Today there are very few jazz musicians who can accommodate the economic costs of large ensembles, including presentations at the major festivals. Houle therefore travels within the small ensemble range, working with the likes Alexander Hawkins, Samuel Blaser, Harris Eisenstadt, Evan Parker, the occasional encounter with the ever-enigmatic Joëlle Léandre, and Delbecq, always Delbecq. One of his latest recorded ensembles is the Genera Sextet. The group was due to tour in Europe in the Fall of 2020 but the COVID-19 pandemic chopped the legs off that long-planned journey, as it has done with countless other musicians.

Viewed from a half-century long view, each new release by Houle is a set of fresh compositions. Deep thought goes into his processes. As he states in the Recoder liner notes, “The music is conceived very methodically, with pitch cells, tonal key areas that are constantly shifting, and rhythmic figures that I stretch and compress following a pre-established yet flexible compositional matrix.” Houle’s flexible matrix approach is key to his music, for it allows his collaborators the freedom they require as improvisers and composers themselves. Such is the subtlety of Houle’s approach that listener may never know what the distinctions are between the exact delivery of what is written and the liberties of improvisation. The on-the- spot invention sounds composed and the composed can equally sound invented.

As discussed earlier in this essay, his thematic inspiration is frequently specific people, poetry, literature, sports, the natural world. To these inspirations, Houle also layers the relations between music and contemporary thinking about codes. He considers, carefully so, who can articulate the compositional needs from the large pool of musicians he collaborates with. Then he spends the requisite time with the musicians mutually exploring the realm of ideas, and from there the recording process will yield its own surprise results.

Coda

Houle stated in an interview with Tony Reif (master-ears owner of Songlines), “The intellect eventually takes a backseat to what the music expresses.” Consider that the compositon “Morning Song 1 (for Ted Byrne)” arose from pondering a single phrase in a Byrne poem, “a broken word/reassembled.” in a Ted Byrne poem, Houle created.

The playing is as enigmatic as an aurora borealis, as powerfully and slowly paced as a sunrise clearing the dew over a stilled mountain lake, an induction into a deep state of introspection. It opens with Houle’s trademark mouthpiece-removed ghostly whistle, a summoning of spirits. This composition demands a state of most-concentrated listening, freedom from distraction including external silence. Either with eyes wide open staring through primordial mists. Or with eyes completely closed, only the music penetrating through the ears to the cortical neurons.

The compositional outlines of “Morning Song 1” are clear, the guitarist bowing his instrument like signals from a distant galaxy, the arco drone of the bass punctuated by irregular plucking, subtle brushwork, and a duet between the bassist and the drummer. With the exception of the melody expressed at the end of the song, a listener will have to work very hard to know where the distinctions lie between the exacting delivery of what is written and the liberties of improvisation.

These distinctions, and not just on “Morning Song 1,” form some of the most enthralling attributes of François Houle’s works, Recoder being a place where the intangibles of conscious thought become transubstantiated into music’s state of wonder.

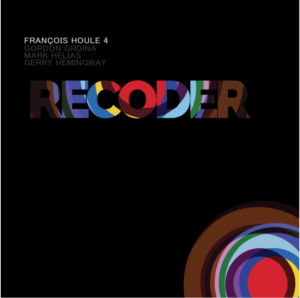

Recoder is published by Songlines SGL 1632-2

Author’s note: While writing this essay, I read Walter Issacson’s Einstein, the Man, the Genius, and the Theory of Relativity. I also re-read Stephen Hawkings’ A Brief History of Time. In end-stage I picked up Gabriel Garcia Marquez’ Love in the Time of Cholera simply to find some simpatico thinking for love in the time of COVID-19. The first sentence reads: “It was inevitable that the scent of bitter almonds always reminded him of the fate of unrequited love.”