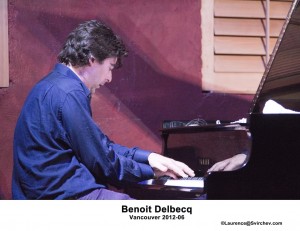

Benoît Delbecq delivered his introduction to the trio gig with his usual charm, grace, and wit through his huge handsome smile by recounting his history of working with François Houle and Marc Ducret. But never before had they played as a trio. When he told the Iron Works audience it was own “party time,” the audience laughed knowingly. All three musicians are well-known to the Vancouver scene and Delbecq’s use of the phrase ‘party time’ was hardly in anye hubba-hubba rebel-rousing sense. They opened with Delbecq’s composition “Le Même Jour” which segued into Ducret’s “l’Histoire”. The rest of the concert consisted of selections from the 2011 Songlines CD Because She Hoped, ending on “Pour Pee Wee.” In this review I’ll look at three compositions, “Because She Hoped,” “Clichés,” and “Le Concombre de Chicoutimi.”

Because She Hoped is a kind of Houle-Delbecq trademark. Its air is delicate, tailored for abstraction, a strong suit for the musicians individually and collectively. The composition floats like white-pillow clouds cusping a mountain top, the musical power residing in its disorientating mist. Delbecq worked the melody several times at the beginning and at the coda, with Houle and Ducret doing the major part of the improvising. In tandem they used clicking devices akin to southern African vocal dialects. At other times. Ducret, in embellishing Houle’s beauteous lines, used single finger slide runs enhanced with foot pedal.

Clichés: At the denouement of “Because She Hoped,” the trio paused and segued into “Clichés” (by Steve Lacy). Houle opened the composition with a solo improvising on the rhythmic line. His first finesse was slap-tonguing, which overlay subtle, semi-hidden circular breathing. He then ran the rhythm through a cycle of rapid-fire circular breathing and returned to the opening gambit. The combination of the two devices gave the piece the momentum and feel of Lacy’s original percussion-choir jam session. He improvised with this two-step cycle three times, accelerating and decelerating, hitting strong overtones. Houle’s execution of “Clichés” was sumptuous, his formidable arsenal unleashed symphonically.

When Delbecq then took over the rhythm at the bass end of the piano, Ducret and Houle jumped in for several cycles of the rhythm before the trio hit the melody. The version was exuberant, fast-paced. Ducret, shaved head in jeans and cowboy boots, swayed his way into the music, at times slapping the strings. If you kept your eyes closed, it was easy to mistake the sound of the guitar for the clarinetist clicking the keys. There were times when Delbecq, grinning devilishly, gobbled up the treasures of the song using cross-hands at the bass end, then rolled his wrist along the keys with thumb in the air. His splashing of right-end notes and and fisted block-smashes moved with the velocity and controlled randomness of Cecil Taylor. Pushing the momentum, Houle even added a train whistle effect using double clarinet. The flourish alone reminded me of the wondrous jazz tradition linking the trio on stage with Ellington via the medium of Lacy.

When Delbecq then took over the rhythm at the bass end of the piano, Ducret and Houle jumped in for several cycles of the rhythm before the trio hit the melody. The version was exuberant, fast-paced. Ducret, shaved head in jeans and cowboy boots, swayed his way into the music, at times slapping the strings. If you kept your eyes closed, it was easy to mistake the sound of the guitar for the clarinetist clicking the keys. There were times when Delbecq, grinning devilishly, gobbled up the treasures of the song using cross-hands at the bass end, then rolled his wrist along the keys with thumb in the air. His splashing of right-end notes and and fisted block-smashes moved with the velocity and controlled randomness of Cecil Taylor. Pushing the momentum, Houle even added a train whistle effect using double clarinet. The flourish alone reminded me of the wondrous jazz tradition linking the trio on stage with Ellington via the medium of Lacy.

In my own state of rapture, I imagined a diaphanous Steve Lacy sitting at the furthest corner of the Iron Works. He had his chin nestled into his right hand, the index finger crested around his mouth. His brow would be furrowed, his eyes twinkling, and he would be smiling benevolently as Delbecq-Houle-Ducret skate their way through the composition’s tricky ellipses. He might even have stuck around to hear Houle read the never-published lyrics of “Clichés” from an original chart dated September 21, 1981 that Lacy gave him:

“Palmiers, baobabs, plages, mer soleil, langoustes, mangues, papayes, gambas, piment, tam-tam, boubous, enfants, pirogues, taxi-brousse, poussière, orage, chant des crapauds, après la pluie, odeurs, cheveux nattés, un serpent sur la route,sueur, rires, mosquées, chèvres, mendiants, champs de mil, 500 transistors en même temps et—– la lune — bons baisers”

One of Lacy’s forte’s was that he adopted lyrics from leading contemporary poets and well as the ancients. Some of his most compelling melodies were composed with the poetry to be rendered exactly as the melody. Irène Aebi was Lacy’s vocalist, singing with an art-song exuberance that was not to the liking of many. But she did the job with the surrealist exactitude Lacy required. Lacy’s liner notes to the 1983 recording of Clichés (hatOLOGY 536) state that the lyrics came from a postcard from Senegal by a certain Aline DuBois. If one goes back to the hatOLOGY versions (there are two concert recordings), listen to how Aebi sublimely phrases “500 transistors en même temps.”

I often wondered why the composition was named “Clichés,” since the music was anything but clichéd. Now it seems clear. Lacy took the postcard clichés and turned them into a complex but hummable melody. That melody is so striking, but the sung words were not easily decipherable, running through my head like those 500 transistor radios blasting at the same time. Now the lyrics are clear and I can secretly sing along when that melody synapses through my neural centers.

“Le Concombre De Chicoutimi” (the Chicoutimi Cucumber) is a lament for was Georges Vézina, a Canadian hockey goalie known for calm demeanor while under pressure. The composition opened with Delbecq running what appeared to be a strip of cloth under the piano strings at the bass end. The see-saw motions, the careful manipulation of the tautness, and the accleration-deceleration stop-start cycle of the cloth set up an eerie drone. Periodically Delbecq struck the bass strings to create a long, deep resonance. Letting the sounds resolve, he then moved the cloth further to the left end of the sound-board and repeated the cycle, this time creating resounding deep bass notes when he struck the strings. Houle used a single clarinet to create an uncanny monotone though the bore, varying it by bouncing the bell of the horn off his calf or blowing into the cavity of the piano, sometimes with tongue slaps.

The total soundscape produced a feeling of disconcerting and vast loneliness, as if a spirit were departing into an enigmatic void. It reminded me of the spooky solitudes found walking alone on windless nights along expanses of mountain grassland in the Montana or Tibetan plateaus, cold light from the achromatic full moon thwarting normal perception.

The total soundscape produced a feeling of disconcerting and vast loneliness, as if a spirit were departing into an enigmatic void. It reminded me of the spooky solitudes found walking alone on windless nights along expanses of mountain grassland in the Montana or Tibetan plateaus, cold light from the achromatic full moon thwarting normal perception.

At four minutes into the this surreal atmosphere, Houle waved his clarinet and they formally stated the magisterial and mournful melody. Its cadence was august, as if a great force has passed out of life. At the end of the first melodic statement, Delbecq briefly flourished his ‘cloth’ and then both he and Houle dropped out leaving Ducret to solo.

Ducret’s solo was free-form, completely outside the structure of the composition. His right hand squeezed notes by sliding grasped thumb and forefinger along the strings, tapping the strings above and below the left hand, leveraging the floor pedal, all to produce unearthly sounds. It was a slow-motion dance, as if time were approaching 00 Kelvin. When Delbecq re-entered delicately with left hand, then going cross-hands, Houle blew softly through double-clarinet, both anchoring an ancient keening that Ducret created. The piece tapered incrementally, as the shoreline disappears when sailing into the ocean, and then faded into an eternal silence.

The music of Delbecq-Houle-Ducret was intense, introspective, pastel-colored, filled with space. It was a perfect concert for those who want their ears, intellects, and hearts filled with sounds refreshingly free of jazz stereotypes, music that springboards from the masters of the past, and into the open arms of the new masters.