On the evening of Monday July 27, 1959, Thelonious Sphere Monk took his working quartet (Charlie Rouse, Sam Jones, Art Taylor) and guest saxophonist Barney Wilen into the Nola Penthouse Sound Studios at 111 W. 57th St., New York City. There he taped eight compositions for the soundtrack of the Roger Vadim film Les Liaisons Dangereuses. The key man for the soundtrack’s realization, Marcel Romano, made it back to Paris with Monk’s tapes in time for a July 31 editing deadline. He also carried a second set of tapes recorded by Art Blakey & the Jazz Messengers playing music composed by Duke Jordan.

The movie was an adaption of the four-volume 1782 epistolary novel by soldier and writer Pierre Choderlos de Laclos describing the elaborate social games of two libertines engaging in sexual seductions that purposefully result in the ruination of the reputations of pure, innocent, and virtuous young people, and ultimately the revenge of fate on the protagonists. The novel was notorious in its time, the scholarship indicating that it was never displayed openly in the homes of its readers. Yet it was also wildly popular, with twenty re-imprints within the first year.

Vadim’s film adaptation was equally sensational due to its perceived prurient content. Initially the French government refused permits for export on the grounds that it portrayed contemporary France in an unfavorable light. The September debut screening, only six weeks after Romano brought the soundtracks to France, was delayed for a few hours and the film actually seized as the result of a lawsuit by France’s Société des Gens de Lettres. The High Priests of the French literary establishment claimed that the film “desecrated a classic.” Advocat François Mitterrand, who went onto become the president of France, and the Société negotiated a ridiculous compromise: 1959 was added to the French title and 1960 to the American release, thus ending the blasphemy. Even the American release was delayed over censorship issues; in an unsuccessful curve-ball, Duke Jordan attempted to stop the film because his music was not properly credited.

With scandal-generating themes from a historic novel and publicity generated from a conservative reaction, Les Liaisons Dangereuses went on to break French film box office records. It didn’t hurt that the protagonists were played by heart-throb Gérard Philipe, and the stunning Jeanne Moreau “at her ravaged best” according to ace American film critic Pauline Kael. It further didn’t hurt that contemporary reviews discussed the jazz soundtrack. While Kael missed the point when she qualified Monk’s music as “background,” she was on the money when she commented about Blakey’s dubbed music in a bacchanal club scene: “Vadim also uses jazz and Negroes and sex all mixed together in a cheap and sensational way that was probably exotic for the French in the 50s.”

Monk’s music is present on approximately 30 minutes of the 111 minute-long film, and several of the most tender moments are scored with solo piano. Robin D. G. Kelley, author of Thelonious Monk, Life and Times of an American Original, states in the liner notes to this CD/vinyl release, “[Monk] and his band delivered extraordinary music that challenged Vadim and Romano’s conception of how a soundtrack functions in film. It is not too much to suggest that Monk transformed what would have been an edgy but relatively standard narrative film into avant-garde cinema.”

And then the Monk tapes simply disappeared. They had never been considered for release on vinyl and were publicly forgotten except for their presence on Vadim’s movie. They lay dormant for 55 years, preserved from the gnawing criticism of mice and that universal solvent, H2O, until found among Marcel Romano’s archives in 2014.

In 1782, France was in prelude mode to its great revolution, a social structure founded upon a degenerating aristocracy and ripe for the collapse of a rotting monarchy. The career of Pierre Choderlos de Laclos was primarily that of a military officer, a man who wrote opera and creative works to spare himself of the boredom of soldiery. At the same time he was adroit in military tactics and even invented a modern artillery shell. Les Liaisons Dangereuses is cryptically subtitled A Collection of Letters from One Social Class for the Instruction of Others. It was a time when basically only the aristocracy, the clergy, and emerging bourgeoisie was literate, the mass of proletarian and farming classes being unschooled. Choderlos de Laclos didn’t take his work lightly. He is quoted as saying, “I resolved to write a book which would continue to cause a stir and echo through the world after I have left it,” an understatement of his historical achievement given not only Vadim’s film but also a 1988 lavish period-piece movie and enduring stage adaptions. Given that he also wrote a treatise on the rights of women to formal education, his book has to be conceived as far more than entertainment on the vanities and less than exemplary lifestyles of the aristocracy.

The 1782 storyline is structured as a series of letters, primarily correspondence between Marquise de Merteuil and the Vicomte de Valmont, in which they plot and counter-plot both as co-conspirators and as foes their seductions and manipulations of people in their social and political arena. Choderlos de Laclos frequently uses military language to describe conquests, attempted kisses as feints designed to leave the object of seduction defenseless.

Vadim cleverly set the film in modern times at a house party, ski chalets, and at Club Chez Michel, a kind of private-members club disguised as a jazz joint, but whose real purpose is for uninhabited alcohol use and sensual self-indulgence out of view of the public (no drugs are in view, for that would have certainly condemned the film in the eyes of European and American censors).

Vadim also retained the device of exchanging of letters between the protagonists as they stage their campaigns, but turned the original protagonists into a married couple, Valmont and Juliette de Merteuil. For the first two-thirds of the film they revel in their ability to stay married even while they purposefully seek pleasure in the arms of others. At one point, Juliette says, “We are honorable people, Valmont. We don’t allow untruths, so destructive for other couples.”

Such tender mercies cannot last. Moreau’s Juliette falsely smiles like a Sun Queen the better to lead her female victims to self-destruction. There are two of them, Cécile de Volanges and Marianne de Tourvel. Both are destined for seduction by Valmont and it is with an already married Marianne that he truly falls in love. Juliette’s heart is cruelly rational, her typical line being, “Seduce her, then drop her in your usual manner.”

Valmont is somewhat of a study in contrast to Juliette. He is an arch-pretender, his voice full of low-pitched romanticisms. He has soft spots even as he matter of factly says of Marianne, “She believes in chastity but will sacrifice it for me.” When the sacrifice of her chastity results in his love for the victim, he hesitates on carrying through “Operation Break-up.” In a tension-filled scene, Juliette dictates a telegram on behalf of Valmont, “I seduced you with pleasure, and I‘m leaving you with no regrets, that’s the way it goes.” Valmont is in agony, he loses his habitual cool, and in the background there is a huge image of an out-of-focus chess piece, a Queen.

This Queen thinks she can command any strategic or tactical social move, and indeed a black Queen standing on the white square of a chessboard is the first image in Les Liaisons Dangereuses. The camera view descends a notch to the name “Jeanne Moreau” in white on top of a black square. Then the name “Gérard Philipe” and the rest of the cast, all on the chessboard. The same chessboard credits “Musique de Thelonious Monk.” The other members of the quartet (Charlie Rouse, Sam Jones, Arthur Taylor and the participation of Barney Wilen) are noted, as are the members of Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. The credits include ‘special sequences’ with Duke Jordan and Kenny Clarke, both of whom briefly appear at club Chez Michel. Kenny Dorham, who also appears in the club scene, is left out of the credits.

But the film does not actually start with imagery but rather with a black screen and the beautiful sound Monk’s “Crepuscule with Nellie,” perhaps the most unusual title in the entire history of jazz. Written specifically for his wife, “crépuscule” is French for twilight or dusk and was suggested by Nica de Koenigswarter.

Vadim and crew were exceedingly detailed when it came to integrating Monk’s music into the film. The float of the credits is timed to end on the last note of “Crepuscule with Nellie.” The soundtrack immediately segues into “Well, You Needn’t” for the opening scene, a cocktail party at the home of Juliette and Valmont. The guests are gossiping about their hosts, revealing that the party’s purpose is to introduce Valmont into social circles that can get him a posting with the United Nations. More than that, it becomes obvious that the charming but essentially conniving Juliette has already paved the way for a lover she is about to drop to get married to the same Cécile de Volanges that she has told Valmont to seduce.

A telephone rings just as “Well, You Needn’t” is ending. Juliette heads into another room to answer and Valmont, standing in front of a record player console, is seen holding a 33 rpm paper sleeve of the 1956 Brilliant Corners album, Monk’s photo clearly seen on the cover. In the time it takes for him to get into the next room with Juliette, “Ba-Lue Bolivar Ba-Lues-Are” begins to play. The record change and the drop of the needle is impeccably timed, a knowledgeable director’s adroit insertion of the music, a delight for any jazz fan.

Around the 17th minute of the movie, Juliette and Valmont are fooling around on their bed and she refuses a kiss. “You are not in the mood?” says he and Juliette responds, “I live by principles, I won’t cheat on my lover, even with you.” Such principles begin one of the parallel plots that impel the film, the seduction of Cécile des Volanges. With Monk soloing fast on “Rhythm-A-Ning,” Valmont exclaims, “But she’s my cousin!” and Juliette response, “And I am your wife, I’m making you a nice little gift. She’s 17, a little awkward, but promising.” No wonder the film was considered scandalous.

When Juliette says, “Here’s my plan,” there begins an strangely out of place drum motif by Art Taylor, “boom, tchk, tchk” seven times over, before Monk kicks in with the piano melody of “Light Blue.” Taylor’s motif is jarring to a jazz-listener’s ear, like a child’s attempt first attempts at an drum accompaniment. In fact, the flat sounding non-resonating “boom, tchk, boom, tchk” had its genesis in a fourteen minute rehearsal track, now revealed as “The Making of Light Blue.” The composition is central to decisive moments in the film.

“The Making of Light Blue” is a study in Monk’s studio method. The track opens with Taylor playing the motif twice, Monk runs a fragment of the melody, and Taylor drops out. Monk says, “Why don’t you keep doin’ what you just doin’, what you doin’ then, yeah, keep doin’ it.” It is the Master of Mumbles speaking, no King’s English in the phraseology, lots of “You dig?” talk, making it abundantly clear what he wants: rudiments. Taylor makes a few attempts at the pattern, but he is definitively nonchalant about it in spite of Monk’s repeated instruction to continue.

Monk keeps stating-not-asking, “Why you stop,” persists in pushing this strange pattern, even at one point lightly chastising Taylor by using the words “dumb motherfucker.” That injects some humor into the session. There are male voices in the background speaking French, a couple of female voices (Nellie Monk and Nica de Koenigswarter) cajoling about lighting a cigarette. Monk keeps pushing, even counting the rhythm out, stating emphatically when and how to accent it. Eventually they get enough down on tape, including with the two horns and the bass parts and then stop to listen to a taped playback. “The Making of Light Blue” is one of those few illuminating moments where we can actually hear Monk’s style of rehearsal leadership and his wonderful voice.

When Marcel Romano visited Monk in July, 1959, he had with him two essentials, a detailed script containing precise timings for each scene that required music, and a copy of the film with some Monk’s studio recordings inserted as suggestions only. Monk would have ignored the script and timings, for as the liner notes explain in detail, there was no time for him to compose new music. Contract negotiations had been going on for a long time, yet Monk procrastinated. He had been subject to intense racial incidents, including a racist police beating in Delaware, a disappearance into a mental hospital in Massachusetts, the deaths of musical colleagues, and the collapse of a tour by The Thelonious Monk Orchestra due to poor press response after the concert at Town Hall, New York City (recorded five months earlier, Riverside RCD30190). He had also begun taking the anti-psychotic drug thorazine.

In contrast to these hardships, Monk had a core of family and friends (Nica de Koenigswarter, manager Harry Columby, and Marcel Romano) surrounding him. Monk, always wary of exploitation, had to feel comfortable before an undertaking. His long-time patron de Koenigswarter took initiative by inviting the Monk family and Romano to her home in New Jersey. There Monk cooked for his kids, played some piano, and challenged Romano to a favored indoor sport, Ping-Pong. Romano had been important to Monk six years earlier on his first visit to Paris, introducing him to Parisian life, the setting for his introduction to de Koenigswarter, taking long walks together, even bringing him to the famous Motsch hat shop where he purchased multiple berets to bring back to New York. The Monk-Romano ping-pong diplomacy may have been a signal of confidence, an important prelude to the signing of the contract. It took two long nights of socializing and family affairs before Monk signed, but for the next evening the magnificent Melodious Thunk was in the studio making his magic.

What certainly impressed Monk was the insertion of his previously recorded music already in the film, only awaiting his score for substitution. Monk would have paid scant attention to the script and its timings but conversely would have paid close attention to the story line and its emotional atmosphere. Kelley states specifically, “He chose the repertoire based on his understanding of the story, and played around with the tempos in order to capture the character’s emotional state or circumstance.”

The tangible proof of Monk’s assimilation and consequent imprint on the editing is his recording of the sacred black anthem, “We’ll Understand it Better By and By” (Reverend Charles A. Tindley, 1906). “By and By” appeals even in the secular sense to the fathomless emotions of men and women faced off against the mysteries of the unknowable. It was composition Monk had played it in his youth as accompanist for a traveling female Pentecostal preacher but never before recorded the plain melody. He would have been struck by the scene in which Valmont and Marianne go to a rustic chapel in the mountains of Switzerland, the lady crossing herself with holy water, and then walk through the snow. While she remains as cold as the snow surrounding them, Valmont goes into partial melt-down, reveals his feelings of falling for her, demonstrating that he is a man caught by the contradictions of his own deceits, attempting to overcome them, but by the end of the film still demonstrating in a drunk stupor his inbred and embedded aristocratic contempt for the rest of humanity. Monk’s rendition must have breathed a wisp of creativity into the producers, for in a stunning and emotionally crushing scene at the end of the film, they portray a betrayed, bereft, and psychologically impaired Marianne humming the melody of “By and By” a cappelo as she packs the deceased Valmont’s suitcase for an imaginary voyage of love to Réunion Island in the Indian Ocean.

While Monk’s music made a huge impact on the film, it’s a good thing that most of his work, except for Marianne’s humming, is placed in the first three-quarters of the film. Plot-wise, the complicated elements come together in a set of explosive sub-endings essentially provoked by the rebellion of a young Danceny. This volatile young man, secretly he and Cécile de Volanges had decided to marry when he finishes his university math program, finds out through Juliette (who is trying to seduce him) that Valmont has seduced and impregnated his Cécile. He confronts Valmont at Club Chez Michel, punches him in the head. Valmont’s head is struck on the fireplace as he falls, and is suddenly dead.

The unfolding and execution of the final scenes is exceedingly clumsy. In today’s digital world, special effects actually can describe violence realistically. In pre-digital film, acting skills and innovative camera angles allowed such scenes to look realistic enough, inducing audiences to willingly suspend disbelief. But in the final accelerating moments, Vadim shorts the audience with his editing. The problem is not that the clumsy delivery of a fist to Valmont’s head, or the equally quick death. It is principally with the context of music at Club Chez Michel. The music dubbed into the film is frenetic stuff, the visuals are table dancing by gloriously stoned young women, drunkenly inert bodies lying next to sexually writhing but clothed bodies. Kenny Clarke, the astounding Klook-a-Mop and intimate of Monk from the Harlem Minton’s days, is doing press rolls out of synchronization with the music Art Blakey recorded (Blakey being another of Monk’s tight friends). The detail with which Vadim treated Monk’s music in the beginning of the film has been replaced by amateurish and shoddy editing.

As for Juliette, her reward is a special living-hell. In the 1782 novel, scandal forces her to the French countryside where she contracts smallpox, her face is scarred, and she becomes an never-again-seductress, blind in one eye. It is not appropriate to give away what actually transpires in Vadim’s version, but Juliette de Merteuil is no longer a subject of curiosity, but one of judgment. She is last portrayed with an inept make-up job, Cécile’s mother saying, “Look at her, her face is the image of her soul.” The subtleties that ran throughout the film are dispelled by a rushed ending, leaving the audiences with nothing but an artificial cherry on top as the last taste of what has become a morality tale, a the teaching that evil people come to no good.

The film itself does not appear to be commercially available in contemporary digital format in North America, only on small screen free web sites. That could change of course with renewed curiosity arising out of issuing the Monk’s soundtrack on CD and vinyl.

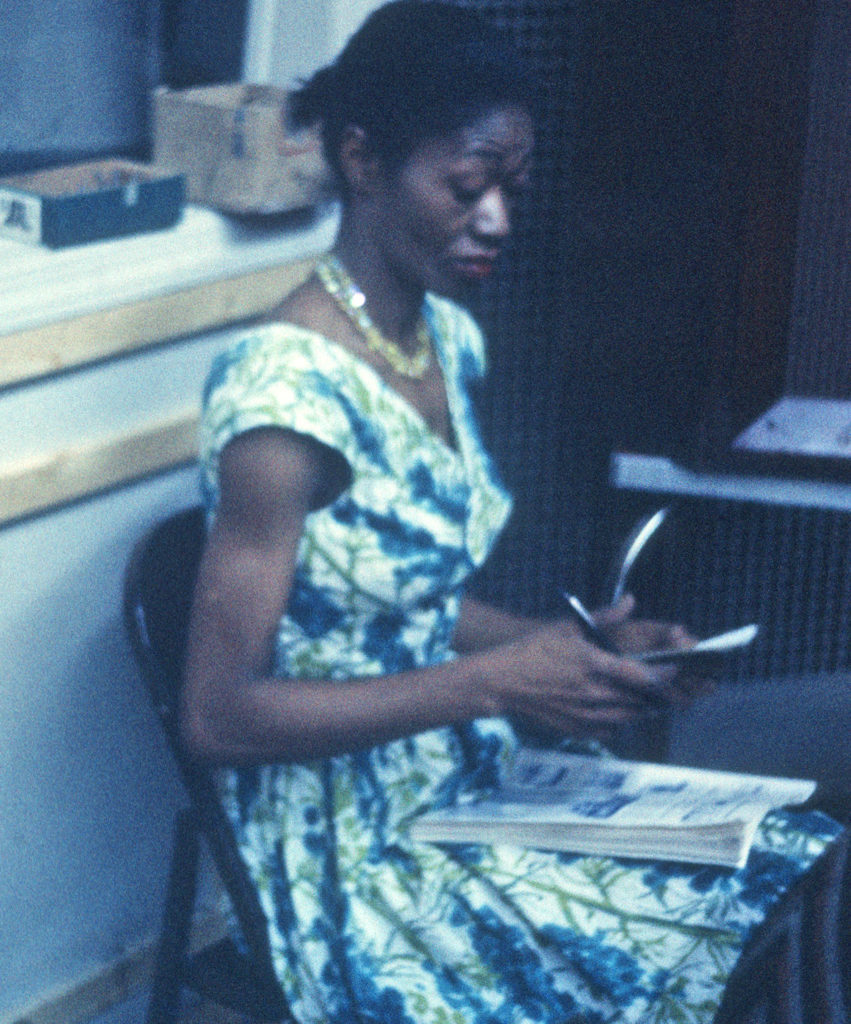

Fifty-five years later what survives without blemish is Monk’s music. The packaging that accompanies the music is a beauty with well-researched essays by the production team (Zev Feldman, François Lê Xuân and Fred Thomas) and Robin Kelley, and previously unseen session photos including Nellie Monk and Nica de Koenigswarter.

The sound quality of Monk’s music in the film was exceptional. Monk’s music was in marked contrast to a pabulum moment, cannons going off in Tchaikovsky’s “1812 Overture” when Cécile tries to get Danceny into her bed. Even at low volume, Monk’s music sets moods by virtue of it being so different from any other soundtrack of the time. The music turns glorious upon hearing the CD full versions of the compositions. There are also some real surprises, sounds of a Monk never before heard, counting in “un, deux, trois, quatre” in beautifully accented French, no mumbles or slurring, for a seven minute version of “Pannonica.”

Then there is “Rhythm-a-ning.” The two versions might be the key band tracks, on both the band charging like a Bucephalus mounted by his commander-in-chief, loose and exact at the same time, perhaps a touch faster than the quartet version recorded a few months earlier on the Thelonious Monk Orchestra at Town Hall, and decidedly more invigorating than the excellent version on Columbia’s Criss Cross album. There’s a palpable excitement coming from each of the musicians, Sam Jones and Art Taylor ferociously hard-driving.

Rouse begins his solo without reference to the melody, adopting the tonal qualities and breathing patterns of Coleman Hawkins, but with longer and more drawn out exploratory inventions (Rouse is a musician consistently underestimated in the jazz literature. For a fuller exploration, see the Misterioso article on Monk’s Japanese Folk Song). Monk closely complements Rouse, deep-ocean tsunami wave bass lines and chime-ringing punctuations. The two-tenor line-up with French saxophonist Barney Wilen is a natural fit.

It was Wilen’s first encounter with Monk, and he sounds as no stranger to his exigent music. Monk allows him the time to stretch out on the up-tempo numbers, a nice contrast with Rouse. He’s also got tonal qualities and breathing patterns that give him a Getz-like quality, making it seem as if the two tenor saxophonists were running tandem histories to pump the ante up. Monk more or less lays out during Wilen’s solos, adding only occasional touches of color, a wonderful vote of confidence in a man who had never played with Monk before. Monk is euphoric on both takes of “Rhythm-a-ning”, making them aesthetically satisfying and the outstanding recorded versions of this composition.

When Monk entered the studio, he had recently been through a living hell of racist police violence, loss of his cabaret license, the death of close friends, the collapse of a breakthrough tour for his Orchestra (which slotted him thereafter into the small group format), and the diagnosis of disease and a prescription drug in an attempt to control his psychosis. He also knew that a Duke Jordan band, not his, would be in the film. Yet the evidence is clear: Les Liaisons Dangereuses is one of his great recordings, outlandishly so. A listener can’t help but feel the unshrouded emotion that comes out of “Crepuscule with Nellie,” “Pannonica,” and “By and By.”

So what was the impulsion to go beyond his norm of transcendent music? Les Liaisons Dangereuses results in tragedy for the licentious, morally decrepit protagonists, a man and woman who have inherited the worst instincts of the old aristocracy. There is only fascination, never sympathy for them. It was equally a tragedy for the pure and innocent victims like Marianne de Tourvel. Recognition of the dynamic tension between these two groups may have been a powerful incentive driving Monk’s enthusiasm in the studio. Monk’s intellectual acumen, his deep spirituality, his sensitivity, and his living in a racist society would certainly have caused him to recognize in Les Liaisons Dangereuses the similar historic, contemporary, and universal dynamics that suppressed his own artistic brilliance, not to mention his ability to support his family.

Artistic incentive would also have been important. Black American jazz musicians had been welcomed in Paris dating back to the First World War when Lt. James Reese Europe presented his 369th Harlem Infantry Regiment band. Monk had loved his previous stay in Paris, even if the critics had been mystified by his music (but he was used to that at home too). Here was an esteemed and fairly wild French film maker expressly reserving critical parts of the film for Monk, a recognition of the type that he could not and never would receive in the United States. Monk didn’t wear a beret in the studio for recording of Les Liaisons Dangereuses. Instead he wore a Chinese farmer’s conical hat. But his work was going to France anyway, with Monk knowing that even if he wouldn’t be seen in the film, he would certainly be heard. Perhaps the recently darkened pathways would be relit. Indeed they were, with Monk touring in the US and Europe regulalry. In 1964 he made it to the cover of Time Magazine, to which he drolly responded on the film about him, Straight, No Chaser, “I’m famous? Ain’t that a bitch?”

Monk is still heard, revered today, a jazz institute named after him. The Vadim film is rarely seen today, but the full Monk recordings can now be heard. Monk’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses is no doubt the reissue of the year, one of Monk’s most important recordings, finally issued fifty-seven years after their creation. Like Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ novel, Monk’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses is one for the ages.

©Laurence@Ssvirchev.com

Note: Laurence Svirchev would like to thank the following people for assistance in understanding Les Liaisons Dangereuses: Benoît Delbecq (https://www.delbecq.net) and François Houle (https://www.francoishoule.ca), Dorothée Zumstein (French playwright). Robin D. G. Kelley kindly clarified some issues directly related to Thelonious Monk’s work methods. The film Les Liaisons Dangereuses 1959/1960 is a complex work of art. The sub-titles rendered in the 1959 version are poorly translated. Source materials include the New York Times, various cinema sites, and of course any errors in this essay are entirely my own.

Wow! What a fascinating article.

Superb piece. I gained a lot of insight. Great to read a writer who has real understanding of both music and film.

An excellent and very interesting piece.

Thank you Laurence – A wonderful reminder of a great film with gorgeous music.

The film can be found on You Tube at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EvsIDDKr7cs

bill smith