“Folk songs transcended the immediate culture” -Bob Dylan

©Laurence@Ssvirchev.com

Give or take a few hundred, two thousand seven hundred years ago there was a blind man who rambled through kingdoms, mountains, and plains, probably swayed to the rhythm of waves on the Mediterranean Sea. He earned his bread, vegetable, meat, wine, warmth, companionship, and bed by telling stories, big bold stories in verse form. Half of his fables were about a hero who spent ten years sailing, or drifting on flotsam of wrecked boats, island-hopping, to get home to Ithaca from the Trojan war. The other half of his work is about the final weeks of that war.

This poet had a gift for composing dramatic stories of incomparable warriors, impossibly beautiful women, jealousies between men, and gods with outsized egos, human emotions of love and bloodthirstiness whose immortal lives ran parallel to those of mortals. Those gods treated mortals as playthings. Poseidon felt insulted by the hero Odysseus, swamped his boats with the waves he controlled. Athena, however, favored him for his fidelity and allowed the hero to reach land after much suffering.

The poet probably lingered for many days and weeks in one location. In today’s lingo, he night be called a “traveling man,” a man “on the road,” a “dream weaver”, or goodness gracious, an “entertainer.” His long form work was spun from repetition and memory. His constant inventions consumed many nights of entertainment, solace, laughter, encouragement, and tears for the tired farmers, weavers, bearers of children, the kings and queens who also toiled in peace, war, perversity, tamed animals, and oversaw annual regimes of planting, harvesting, and preserving. The form of his poetry was epic lines of sinuous and cohesive song, his vocal meter and sometimes twisted rhymes were most likely accompanied by the lyre. Recitation or song-form we don’t know

The name of that primeval enigma was Homer. He may have been two different men according to comparative research. There was a centuries-long time gap between when he actually recited and sang his words and when they were written down. All the extant written versions of the Iliad and the Odyssey are remarkably similar, so his work must have been precisely memorized by countless people and passed along as part of oral tradition.

But in the real sense none of this matters because the poetics Homer laid down in the Odyssey and the Iliad form the base geology of western literature. War and peace, love and love in vain, honor and vengeance, heroism and despicable behavior among combatants, the need to get home and protect family and pastoral rights, the the fundamentals of human emotion and being, these subjects are the poetics of Homer.

Prizes have always been given for literature and inevitably institutions like the Swedish Academy came into being to celebrate the intellectual accomplishments of scientists and artists. The announcements of the Swedish Academy are nothing more than a one-sentence rationale on the significance of the artist’s work. In 2016 the Nobel Prize for Literature prize was awarded to Bob Dylan “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” The rationale is not ambiguous, and those interested in its veracity can nod heads in agreement or disagreement, but one thing is clear. Never before had a performing musician been awarded the Nobel. The Swedish Academy, typically perceived as staid, had broken with tradition and recognized the obvious.

Professor Sara Danius, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy, told journalists that the Academy had broken no tradition by making the award to a working musician. Her press conference comparison was the literature of Homer and Sappho, “who wrote poetic texts meant to be listened to and performed, often with musical instruments….Dylan can be read and listened to.”

Do the distinctions between reading and listening, or poetry, recital, setting words to music hold water? Both are forms of communication; authors regularly read excerpts of their works to audiences. For most of human history, there was only oral tradition, tall tales told at castle banquets or around campfires. Long-distance communication was the sound of a drum, or a runner with a memorized message. Later, stories or song could be transcribed and printed onto papyrus, then later into books, then later printed in multiple copies by machinery. Only in the last one hundred forty years has the oral and musical tradition become realized in the form of sound recordings. Somehow, by force of their literary integrity and their close relation to human emotions and aspirations, the work of literati like Homer and Sappho has survived all these centuries. Perhaps Professor Sara Danius, by simplifying the distinction between reading and listening, was taking it easy on a press whose function is daily dispatches.

Bob Dylan has been performing since he was a kid learning his craft in the weary proletarian town of Hibbing, Minnesota, then wandering the USA and the world over for over five and half decades of composing, performing, and publishing. One of those publications is Bob Dylan, The Lyrics: 1961-2012 (Simon & Schuster). Another is his crypto-incisive autobiography Chronicles, Volume One (2004).

Chronicles is no straight-line chronology any more than his songs are straightforward. It is rather a discussion of how the man thinks, how he situates his songs. He wrote:

“I had nothing to do with representing any kind of civilization…. I was more a cowpuncher than Pied Piper.”

Straight-talk from this particular cowpuncher is testament-style prophesying with lines like “Even the President of the United States must sometimes have to stand naked,” a statement that never seems to lose its contemporaneity.

Dylan is a prodigious reader and listener, who pays homage to writers, musicians, and song writers who influenced his thinking. They are people as disparate as Cecil Taylor, with whom he once played “Water is Wide” at a coffee house on Bleecker St. in Greenwich Village (“Cecil could play regular piano if he wanted to,” he says). One afternoon he dropped into the Blue Note club to listen to Thelonious Sphere Monk working out ideas at the piano. When Dylan told the Monk he played folk music, Monk’s response was, “We all play folk music.” Out of this minor chord, Dylan writes an astute literary statement, “Monk was in his own dynamic universe even when he dawdled around. Even then he summoned magic shadows into being.” Now ain’t that provocative and insightful?

The jazz influence was not only from his earliest years in New York City. Chronicles recounts the time in 1987, while while rehearsing for shows with the Grateful Dead, that “My own songs had become strangers to me.” Dylan writes about himself as if he had assumed the power of a two cylinder back-yard lawnmower. Then one night while taking a break from the rehearsals he went for a walk. He found himself in a small bar listening to a piano trio with a vocalist who reminded him of Billy Eckstine. The unnamed vocalist had a natural energy that opened a mental gate for Dylan, rejuvenated his lost power. He never identifies the vocal technique he recognized and adopted from that anonymous singer but he says, “Something became unhinged….I had that old jazz singer to thank.”

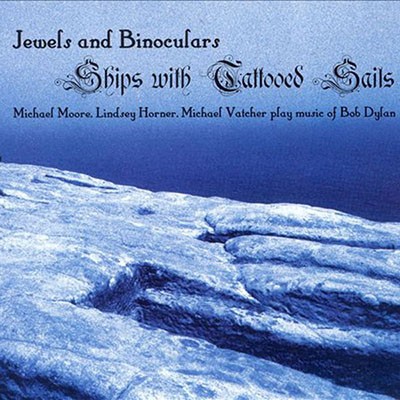

In spite of the influence of the jazz world on Dylan, his influence on the jazz world has been negligible. A few people have recorded individual compositions, but only one group, “Jewels and Binoculars” has paid significant attention to Dylan’s music. At one point in time, the intricate songs of people like Harold Arlen, Rodgers and Hammerstein, Johnny Mercer were important vehicles for many jazz musicians. “Jewels and Binoculars” returned to that tradition. Between 2000 to 2008, the band had a good run, putting out three CDs of Dylan’s music, and performing regularly.

The band was composed of Lindsey Horner (leader, bass, principle arranger), Michael Moore (reeds), and Michael Vatcher (percussion). Their music was sometimes straight renditions of the melodic content, but much of it was extensive extemporization, with occasional drifts into outright transformation. There were emotionally-drenched versions, such as “With God on Our Side” or near-to-unrecognizable takes on compositions, such as “Highway 61 Revisited.” Aside from their stunning renditions of the music of Bob Dylan, “Jewels and Binoculars” showed that Dylan’s poetry and music contains the structural elements that permit substantial improvisation independent of the words themselves. (Read below Misterioso’s recent interview with Lindsey Horner on how the music was arranged).

Dylan’s encounters with the jazz masters is written as a minor side of his influences. He spends chunks of the book discussing Robert Johnson, who influenced the writing of “Highway 61 Revisited,” like this: “The stabbing sounds from the guitar could almost break a window. When Johnson started singing, seems like the guy could’ve sprung from the head of Zeus in full armor.” He writes about the Staple Singers, how Woody Guthrie painted with words and “made every word” count.” There’s the tale of intense struggle writing the songs for a failed Archibald MacLeish play, the heart-rending, brutally emotional, and structurally simple songs of Johnny Cash and Hank Williams. This is a book to be read slowly, a kind of a map but not a guidebook on American culture. Who talks anymore about seminal characters like Dave van Ronk anymore but Bob Dylan? This cat Dylan has no answers but his poetry poses questions whose answers are to be found within yourself, makes each person who listens into their own oracle (“Don’t follow leaders, watch your parking meters”).

The structure of Chronicles is akin to an extended improvisation in which the creative musician, no matter how he far he explores, comes back to the ‘one’. There is call and response between page one and the last few pages. Chronicles begins with discussion of Lou Levy, the man who was his first publisher. Paragraph one deals with Levy taking Dylan to see the recording studio where Bill Haley and His Comets recorded “Rock Around the Clock” and having lunch at boxer Jack Dempsey’s restaurant just after Dylan had signed his first recording contract. In its last pages Chronicles ellipses back to the beginning, with Levy asking Dylan if he wrote any songs about baseball players. The talk of baseball leads to running the names of great Americans who came from the Minnesota that Dylan had just left, people such as Charles Lindbergh, Babe Ruth, and Sinclair Lewis, the first American to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

He says of his future:

“It was strange world that would unfold, a thunderhead of a world with jagged lightening edges. Many got it wrong and never did get it right. I went straight into it. It was wide-open thing for sure, not only was it not run by God, but wasn’t run by the devil either.”

How true, how true, and therein lies, in succinct form, the allure of Dylan’s poetry as song form, open ended like a Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization, something that never goes away and provides no answers, only suggestions at solutions.

From day one, Dylan has been a controversial character, frequently portrayed in the media as a self-contrived ego-maniac. He appears to be naturally aloof, alive and well only in the world of music and art. Yet in reading his rare public interviews and speeches he has been exceedingly straightforward, genuinely grateful of the chance to speak to a thoughtful audience or interviewer, thankful to his sponsors.

For the rest of the world, it’s a ‘leave me alone, I’m a private man” attitude. It’s his ideas, the provocative songwriting that no one can successfully interpret except for themselves, his imagery formed from the natural world of harsh winters in rural Minnesota and the towering intellectual hammer of urban New York City, incantations that leave no answers to those questions he posed in the beginning of his career with songs like “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”, “Blowing in the Wind”, and the late-in-the-game “Tempest”, a long-form, forty-five verse song on the sinking of the Titanic. Witness this:

“The ship was going under

The universe had opened wide

The roll was called up yonder

The angels turned aside.”

The above citation from “Tempest” is an example of Dylan’ simple and traditional verse form, sea-chanty stuff. The precision to be found in Dylan’s songwriting is structural acuity, a devotion to meter in which the free flow and frequently cryptic lyric fits the song-form, akin to the complexity of rigged sails on an ancient mariner’s vessel that become adjusted according the thrust of wind and direction of the sea.

In one of his rare contemporary interviews Dylan stated,

“What I do that a lot of other writers don’t do is take a concept and line I really want to get into a song and if I can’t figure out for the life of me how to simplify it, I’ll just take it all — lock, stock and barrel — and figure out how to sing it so it fits the rhyming scheme. I would prefer to do that rather than bust it down or lose it because I can’t rhyme it.”

In an early 1964 interview with music critic Nat Hentoff, Dylan stated,

“It’s hard being free in a song—getting it all in. Songs are so confining. Woody Guthrie told me once that songs don’t have to rhyme—that they don’t have to do anything like that. But it’s not true. A song has to have some kind of form to fit into the music. You can bend the words and the meter, but it still has to fit somehow. I’ve been getting freer in the songs I write, but I still feel confined. That’s why I write a lot of poetry—if that’s the word. Poetry can make its own form.”

Just one example only: try reading these two lines aloud without reference to the music:

“Ain’t it just like the night to play tricks when you’re trying to be so quiet?

We sit here stranded, though we’re all doin’ our best to deny it.”

–Visions of Johanna

Reading it straight in plain voice, the two lines resolve simply and elegantly, even more simply when read as four lines. Dylan’s sung metric throws the ordinary meter off by causing an internal split-emphasis within each of the two lines. The setting of “Visions of Johanna” is night-time in New York City, but any restless night will do. With the emphasis on the word ‘tricks’, it is rendered it as mysterious as an aurora borealis. Imagine being around a campfire a’way north of Minnesota on a windless star-studded night, where the northern lights do indeed play tricks on human consciousness, maybe making us lonely, speculating how infinitesimally small we are in the universe, driving a being into melancholy or to the state of wonderment.

There was surprise reaction when the Swedish Academy made their announcement and joyful response in many circles. Perhaps the most laudable and fun-poking comment was made by Leonard Cohen: Bob Dylan’s winning the Nobel Prize for Literature “is like pinning a medal on Mount Everest for being the highest mountain.” On a personal note, I was driving down a long road with a German pianist, who exclaimed “Fantastic!” We laughingly spent the rest of our road trip fitting Bob Dylan expressions into our own free-roaming conversations.

What should have been a resounding hurrah that echoed across mountain valleys and transmitted like traditional African drumming or Native American smoke signals became a cold wind from big media. Multitudes of journalists went over the top in slagging the Nobel Committee, and then in slagging Dylan himself. Dylan didn’t immediately respond to the news. There was a sound of silence. With no genuflections or sound bites of gratitude from Dylan, the New York Times, Washington Post and the Guardian published articles calling Dylan ungrateful, snobbish, and arrogant.

Can’t a man enjoy a little peace, savor the honor, reflect a little, and get back to work?

The couth-less points of view in the press ran something like this: songs are not literature; he has no gratitude for being awarded the Prize; other writers are more deserving; and that most pedantic of arguments, he doesn’t need the money. The last of these is not worth commenting on except that it appeared so frequently, particularly in readers’ comments. The logic is that only a poverty-stricken writer should get a literary prize. It is almost embarrassing to point out that prizes such as the Nobel are based on a life-time of influential achievement, not on an artist’s or scientist’s ability to buy a cup of coffee. Writing in 2013, Peter England, former Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy, stated, “The prize is always based on an overall assessment. It’s a life’s work that is rewarded, not individual books”.

The argument that other writers are more deserving happens every year, a tiresome buzz saw, a mosquito-like annoyance that just won’t fly away. There are plenty of writers around the world from different countries writing in a plentitude of languages who turn out great literature. The deliberations of the Swedish Academy are secret so no comparison to other nominees can be made, only guessed at. It’s a dynamic that creates endless speculation resulting in some very good writers getting the benefit of publicity.

Some journalists slagged Dylan because he held off from a public expression of acceptance and gratitude. The Swedish Academy itself kind of shrugged their institutional shoulders when he didn’t immediately return phone calls. This institution deals with all kinds of personalities and they are quite used to intellectuals who do not fit the norm. But the American and British press became empty-headed with his presumed ingratitude. The issue reduced itself to ‘If we can’t get the goods from Bob Dylan’ mouth, we still need a story. How dare he deny us? We need a story and we want it this instant!’

Maybe Bob Dylan was recovering from dental surgery, maybe he was in the midst of writing new songs, re-rigging old ones, buying a new hat (he has great taste in lids). Maybe he was motoring on a Triumph savoring some Americana on a back-road. In a 1964 New Yorker Magazine article by the music critic Nat Hentoff, Dylan stated, “…Being noticed can be a weight. So I disappear a lot. I go to places where I’m not going to be noticed.”

The Swedish Academy calls the winner of a prize a half-hour before their press conference announcements, but where is the law or decorum that says you have to answer the phone just because it’s ringing? Was it a home phone with no one on the property, or did the mobile call screen read “Swedish Academy” or “Unknown Caller?” Neither Dylan nor the Swedish Academy has ever told the story, and why should they?

Can’t a man just enjoy a little peace when he’s disappeared himself?

It’s all immaterial, because Bob Dylan seems to be just one of those people who does things on his own time and at his own speed. He learned early in the game that press reviews don’t necessarily sell recordings or tickets. He also found out that ignoring the press -or even giddily provoking them- got him stories anyway. One of the ways he learned this can be seen in the main film about his early career, D. A. Pennebaker’s 1967 Don’t Look Back. In London, England, Dylan at age 23 queries reporters and determines that most of the them hadn’t listened to his music. Instead, they asked inane questions about his being a leader of a social movement. At one press conference Dylan simultaneously charms and lampoons the reporters by holding a mock-up of a huge light bulb. The British press corps obliges, dopily trying to discern the symbolism of the prop. It was positively beatelesque, absurd in the way the same press pestered John-Paul-George-Ringo with inane questions about their haircuts, but never about their music.

Take the dynamic forward fifty years to 2016-12-09 when under the headline “Dylan, Polite? It Ain’t Him, Babe.” Sarah Lyall, a veteran New York Times journalist wrote, “He did not attend the traditional news conference. He did not deliver the traditional lecture. He did not make the traditional visit to a local school, or take part in the traditional fancy dinner with the Swedish Academy”.

The headline is pure dupery. On the rare occasions when Bob Dylan addresses the public, he is extraordinarily polite and gracious, as if he knows what really counts to the human heart. Witness his interview with the American Association of Retired People, where speaking of his CD Shadows in the Night he states,

“If it were up to me, I’d give you the records for nothing, and you give them to every [reader of your] magazine.”

Here is an excerpt from the speech Dylan had delivered on his behalf by the United States Ambassador to Sweden Azita Raji at the Nobel Banquet:

“I extend my warmest greetings to the members of the Swedish Academy and to all of the other distinguished guests in attendance tonight. I’m sorry I can’t be with you in person, but please know that I am most definitely with you in spirit and honored to be receiving such a prestigious prize. Being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature is something I never could have imagined or seen coming.”

The key word in Lyall’s article is not “polite.” It is the four-times mentioned word “traditional.” There is zero content in the article about his music. The veteran journalist is more interested in following -in lock step- the half-century old journalistic stereotype of Dylan’s symbolic value, studiously ignoring the reason for Dylan’s being awarded the Prize.

In his speech at the MusiCares Person of the Year 2015, Dylan does his own four-play on the word, saying,

“[My] songs didn’t come out of thin air. I didn’t just make them up out of whole cloth. Contrary to what Lou Levy said, there was a precedent. It all came out of traditional music: traditional folk music, traditional rock & roll, and traditional big-band swing orchestra music. I learned lyrics and how to write them from listening to folk songs. And I played them, and I met other people that played them, back when nobody was doing it. Sang nothing but these folk songs, and they gave me the code for everything that’s fair game, that everything belongs to everyone.”

Being a public figure, Dylan becomes fair game for speculation, and that includes the charge that he is not polite, a code word for his unwillingness to play the contrived game of public relations. Dylan has the public reputation as a fiercely private man, a man of supreme ego who shields himself from public view. It all becomes clear in his discussions of invasions of privacy while raising his family in Woodstock, NY. Delusional hordes would gather outside his home demanding that he come forth and lead them to some vague political goal as if he were a messiah who wrote songs to stir them up. In spite of such adulation, he states again and again that he is just a song writer and that what he has accomplished comes out of the great canon of art, literature, and song that comes before him. That may be what Dylan really thinks, but the incidents that he points out mean just one thing: Dylan’s writing and recordings get under peoples’ skin.

He put it succinctly in his speech to Musicares:

“Well you know, I just thought I was doing something natural, but right from the start, my songs were divisive for some reason. They divided people. I never knew why. Some got angered, others loved them. Didn’t know why my songs had detractors and supporters. A strange environment to have to throw your songs into, but I did it anyway.”

The strangest -and strongly stated- notion among all the negative press was that songs cannot be literature. Rolling Stone magazine printed a cranky rant that contains within it its own seeds of destruction: “Of course it’s not poetry, not even sung poetry. It’s songwriting, it’s storytelling, it’s electric noise, it’s a bard exploiting the new-media inventions of his time (amplifiers, microphones, recording studios, radio) for literary performance the way playwrights or screenwriters once did.” But here is the illogical oddity: the title to the article is “Why Bob Dylan Deserves His Nobel Prize.”

Rolling Stone Magazine carries no pedigree for the academic literati, but some intellectuals who should have known better twisted their thinking into a Gordian Knot over songs as literature. Representative of such a response was an article under a New York Times headline “Why Bob Dylan Shouldn’t Have Gotten a Nobel.” Author and editor Anna North wrote, “Bob Dylan does not deserve the Nobel Prize in Literature…the Nobel committee is choosing not to award it to a writer.”

The thrust of her argument is contained in, “Yes, Mr. Dylan is a brilliant lyricist. Yes, he has written a book of prose poetry and an autobiography. Yes, it is possible to analyze his lyrics as poetry. But Mr. Dylan’s writing is inseparable from his music. He is great because he is a great musician, and when the Nobel committee gives the literature prize to a musician, it misses the opportunity to honor a writer.” North goes on to suggest several writers who could have been given the prize in lieu of a musician.

Some things haven’t changed. Bob Dylan is still getting stones thrown at him for playing a guitar.

North has a distinctively-twisted logic, to which an Alexandrian blade could be swung with nonchalance to sever it. Consider several easy-to- answer questions. Is the domain of Bob Dylan’s work founded upon words? Does he compose in traditional and non-traditional poetic forms? Does he have a profound body of work written over the course of more than half a century? Has Dylan “created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition?” The answer to each question inevitably, “Yes.” It just won’t do to confound the issue of writing by introducing the concepts of singing and music. If an equivalent of the Nobel Prize for Literature had existed 2,700 years ago, that blind man Homer may not have been crowned by laurel leaves, he would have been eliminated from consideration by some cantankerous critic for daring to sing.

The Nobel Prize for Literature gets cage-rattling press every year from all kinds of folk weighing in on who should have won. If Bob Dylan had confined his work strictly to the written form, not by a country mile would he be known to millions of people worldwide. Contemporary poets are not particularly well known except to the literati and academia. But as a poet who sings and performs his work as music Dylan commands an international stage with millions of people of all cultures and nationalities, something that very few poets can claim.

When thinking of the brilliant authors who have won the Prize, like Hesse, Hemingway, Mahfouz, Camus, Pasternak, Llosa, Neruda, Mo Yan, Márquez, lifelong readers will remember the names of their books and the wonderful stories they have told. But recalling individual lines from their writing is rare, other than perhaps phrases from from T.S. Elliot (“In the room the women come and go/ Talking of Michelangelo”) and the non-Nobel contender who wrote, “There was only one catch, and that was Catch-22.”

With Bob Dylan there are dozens of lines that can easily occur to any lover of music, song, and literature, phrases that plug into the mind and never leave. Bob Dylan’s sung poetry simply has entered the international public consciousness, maybe like no other writer of the last century has. Consider the following lines as a sample of what multitudes can sing from memory:

“There’s no success like failure and failure’s no success at all.”

“You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.”

“He not busy being born is busy dying.”

“Tangled up in blue.”

“Manipulator of crowds, you’re a dream twister.”

“If it keep on rainin’, the levee gonna break.”

“Heard ten thousand whisperin’ and nobody listening.”

Enigmas amplified, luciferous, timeless, unforgettable stuff formed in the crucible of modern literary thinking is the literature of Bob Dylan.

Sources:

–http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/2016/

–http://articles.latimes.com/2004/apr/04/entertainment/ca-dylan04

–https://www.nobelprize.org/nomination/literature/questions-peter-englund-2013.html

–https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/09/arts/bob-dylan-nobel-prize-sweden.html

–https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/2016/dylan-speech.html

–http://www.rollingstone.com/music/features/why-bob-dylan-deserves-his-nobel-prize-w444799

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/26/opinion/the-meaning-of-bob-dylans-silence.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/13/opinion/why-bob-dylan-shouldnt-have-gotten-a-nobel.html

Note from Laurence Svirchev: the best essay on Bob Dylan I read while researching this article was by a 1964 piece by Nat Hentoff, a writer known to anyone who reads the jazz literature:

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1964/10/24/the-crackin-shakin-breakin-sounds

Supplement: Interview with Lindsey Horner

Laurence Svirchev: How did you arrange “Highway 61 Revisited”?

Lindsey Horner: Whenever I did an arrangement, I took a large piece of score paper, the kind you would use to write for an ensemble like an orchestra or big band, and wrote all the words down starting on the left side of the paper. As you might imagine, sometimes this took up quite a bit of room. I would then start paying attention to the meter and rhythm of those words and see what kind of ideas would emerge. Sometimes it would be a melodic line, sometimes a bass figure, sometimes a harmonic progression or sound. The only thing I didn’t pay any attention to was the original version as I had no interest in “covering” the tune. I preferred to re-imagine and re-interpret it. Ideas would always come without exception and without having to wait too long, so strong are Dylan’s words and ideas.

In the case of Highway 61, the short, vernacular nature of the phrases being used to describe biblical and absurdist events suggested a descending, chromatic bass line that never comes to rest until the “Highway 61” at the end of each verse. It’s a 16 bar blues which draws out the lines longer than the more usual 12 bar blues would do. Sometimes we would extend the end/beginning so that it would be 18 or 20 bars. We ended up playing it in Gb for no particular reason that I can remember other than that it seemed to sound good there and was fun to play.

LS: How did you arrange “Dark Eyes”? In some of the songs on the three CDs, I hear Michael Moore kind of trailing off at what would be the end of a sung phrase, leaving the last few words implied. I also hear you and Michael Moore alternating what would be the sung lines in the original. That lends a nice tension-relaxation to the music.

LH: I hear “Dark Eyes” as being in the tradition of an Irish or Scottish ballad, like “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall”, “Farewell Angelina” or “The Times They are a-Changin’”. I had done the arrangement with the Irish singer/songwriter, Susan McKeown on our duo record, “Mighty Rain” back in 1997. Apart from the incredible and expressive lyrics, I took inspiration from Dylan’s guitar part which is one of his more interesting ones, almost like something that Richard Thompson or some other brilliant guitarist might come up with. I imagined what it would sound like on harp, out of the bardic tradition. Michael Vatcher had that odd, zither-like instrument that he used in a very unique manner and he ran with it.

LS: “Blind Wille McTell” & “With God on Our Side” hit the emotions pretty hard. “With God on Our Side” actually sounds like there is a battle going on. What made you treat them that way?

LH: “Blind Willie McTell” is a true American masterpiece and one of Dylan’s greatest songs – not just one of his best songs, but one of the greatest, like “Blowin’ in the Wind” or “Like a Rolling Stone.” It’s more than a song, it’s a cultural touchstone and work of art. Many people are mystified that he left it off the album for which it was intended (“Infidels”). But to me, that sums up just how many great songs he writes. He has probably thrown out scores of songs any one of which are better than other artists’ best work, as the continuing Bootleg Series attests.

Bill Frisell played on a few compositions like “Blind Wille McTell” for the third CD. I wanted the vibe of the tune to come through and to give space for Bill’s guitar to state the melody freely. When we played it in trio, same thing. I wanted it to be unhurried and weighty and to have something of the “cumulative effect” that the verses of Dylan’s version have.

Doing “With God on Our Side” that way was Michael Moore’s idea and I think he wanted the fact that it is all about war and the justifications thereof to be readily apparent.

LS: Did you arrange specific instrumentation for Michael Moore and Michael Vatcher? Vatcher has an unorthodox sound on the kit and he also uses all sorts or ornamental percussion devices right out of the folk tradition.

LH: Sometimes I might suggest, “I hear this on alto” or “maybe play cymbals on this section”, but for the most part I let the guys figure out what worked best, like the collaborative effort the band was at its’ best. If something wasn’t working or didn’t feel right, we’d try something else – or drop it altogether. Michael Vatcher is a somewhat unconventional drummer (I think he’d agree with that). He’s also a big guy and one thing I noticed about him was how good the drums sounded when he really hit them hard. I think that was something he didn’t get much chance to do in other contexts and I encouraged him to do that (check him out on “Father of Night” and “Highway 61”, for example).

LS: I’m interested in what you hear in Dylan’s music out of the European tradition transposed to America. From what I read in your biography, you might be the best musician I know of to articulate that, given your vast experience with folk music. This includes the structural elements.

LH: As I hear it, Dylan steeped himself in the full range of American music, especially that which came from the British Isles, (England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales) and the blues. There’s a very telling segment in the Scorcese documentary where he openly and affectionately credits the Clancy Brothers for introducing him to that ballad tradition and all that lay behind it. Liam Clancy confirms this and says something to the effect that, “We gave him what we knew and he gave it back to us transformed”. A number of his early songs are actual traditional tunes that he has put his new, astonishing poetic words to (“Hard Rain”, “Restless Farewell”, “Farewell Angelina”, etc), and then there is “When the Ship Comes In”, an amazing and overlooked tune that Liam Clancy himself sang in concert until his dying day. This is clearly a “modern traditional” ballad out of that tradition, imagery completely modern and utterly timeless – like all great folk tunes.

Lindsey Horner’s Website: http://www.lindseyhorner.com/

Jewels & Binoculars’ “Ships with Tattooed Sails” is available from Mr. Horner’s website and

https://www.cdbaby.com/cd/jewelsbinoculars

Jewels & Binoculars “Floater” (Ramboy 20):

http://www.ramboyrecordings.com/ramboy20/ramboy20.htm

“Jewels & Binoculars” (Ramboy 15):