© Laurence Svirchev

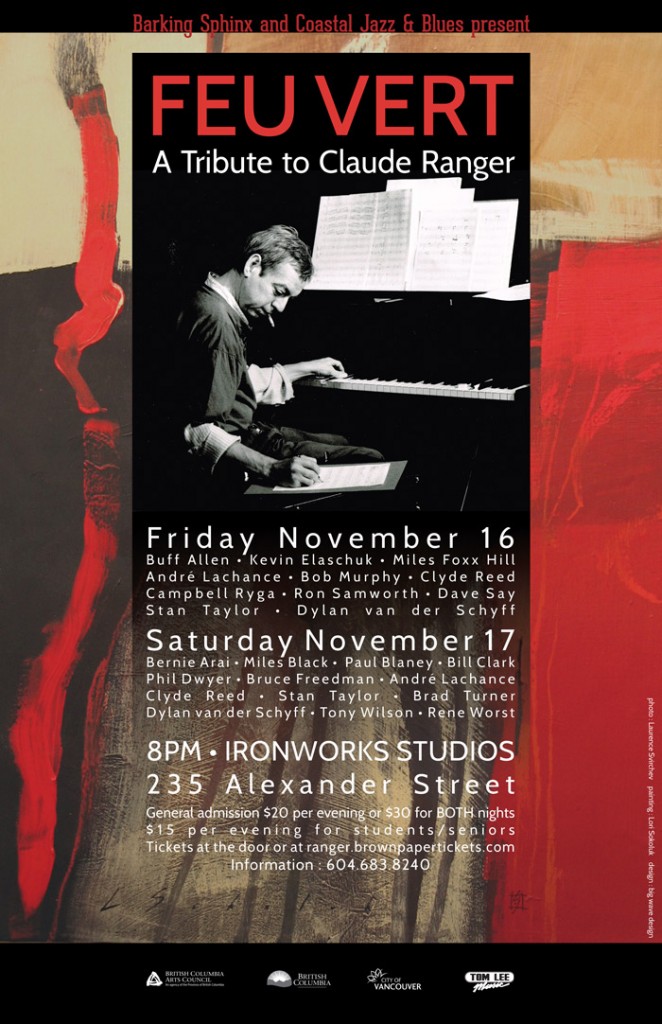

Note: “Feu Vert -A Tribute to ClaudeRanger” will be held on November 16 & 17 2012 at the Ironworks, 235 Alexander St, Vancouver BC. See the poster at the end of this article, first published in 1991, revised 2012 with photos from the Misterioso archives.

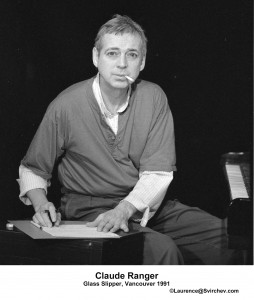

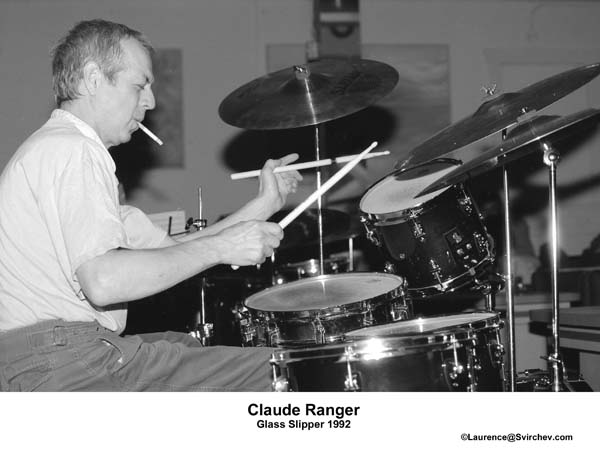

The cigarette dangles at a dangerous angle from the drummer’s lips, a faint cloud of smoke arising every few off-beats. The ash grows to an inch, then more, glued to the glow that produces it. The image of the cigarette is so strong the first time listener may be distracted from the fire of the music, just wishing the ash would fall.

The cigarette dangles at a dangerous angle from the drummer’s lips, a faint cloud of smoke arising every few off-beats. The ash grows to an inch, then more, glued to the glow that produces it. The image of the cigarette is so strong the first time listener may be distracted from the fire of the music, just wishing the ash would fall.

But the ash stays in place, held there by the gravity of Claude Ranger. Newton’s force of gravity makes everything fall, but the absolute musicality of Claude Ranger displaces and re-defines the ordinary laws of gravity, light, color and emotion. Claude Ranger conducting from the drum kit is as swift, smooth, and unerringly attractive as the vortex of the maelstrom. There is no escape, for he is a Black Hole of the music cosmos, a densely compact body of wonder and warmth, a man whose force of gravity is so strong he re-shapes the fourth dimension, time itself, to the rhythm he wishes. He does it just as easily as you or I bend a paper clip. Claude Ranger is an E=mc2 of musicality, a man who has surpassed the theory of relativity. But he also wears peach-colored and impressionistic shirts.

While virtually unknown to the listening public, Claude Ranger long ago acquired the status of a living myth among musicians. There are a thousand stories of his ability to project the range of human beauty through the medium of his drumming. There is the universal admiration of his virtuosity at the drums, but there are also the stories of the Toronto hierarchal establishment which would not hire him due to his refusal to compromise the music. And then there are the stories of the young players he continually takes under his leadership. The stories are not told by Claude Ranger. He is a modest, straight-forward man. He does not hang out; after the gig, he is gone, and this just increases the mystery about this musician.

‘Un gars bien ordinaire’ originally from Montreal, his name has a soft pronunciation, “Rahn-geh”. At home his music collection contains Debussy, Stravinsky, Ravel, impressionistic classicists. He plays in a variety of contexts in Vancouver but has just received funding from the Canada Council which will permit him to devote all his energies to writing his suite Stars In Tears. Sketches from the suite are currently in the repertoire of the Jade Orchestra.

“I always liked the color jade,” Mr. Ranger says. “I don’t mean the stone, I mean the color. Jade has all the light; it’s like water, like fire. It’s warm and it’s cool. Hey, you know the Miles Davis tune, the one Bill Evans wrote, ‘Blue in Green’? That’s a jade color. My music is something you can see, like Debussy’s ‘La Mer’. You can feel the ocean in the music.”

Saturday, June 3, 1990, Stage Two, Gastown. The rain always breaks every year for the duMaurier International Jazz Festival. There’s a warm sun and it’s also Jade’s major public debut.

The audience is butter-soft from the six o’clock sun at their backs, but hearts are melting from the melody of the final number, ‘Wood Nymph’. There is a long tenor saxophone solo in this sentimental piece. If you’re newly in love, you know the glow this tune inspires without even having to hear it. If your heart has recently been broken, then hearing ‘Wood Nymph’ will make you fall apart one more time. And if love is just around the corner, ‘Wood Nymph’ will quicken your step.

I can’t refrain from telling Mr. Ranger a few days later, “That tune is so beautiful, people in the audience were weeping openly. They weren’t even trying to hide their tears.” Mr. Ranger is well aware of the power of his music. He responds laconically, “I re-arranged the tune. Next time they will cry even more.”

I can’t refrain from telling Mr. Ranger a few days later, “That tune is so beautiful, people in the audience were weeping openly. They weren’t even trying to hide their tears.” Mr. Ranger is well aware of the power of his music. He responds laconically, “I re-arranged the tune. Next time they will cry even more.”

The Jade Orchestra started in April 1989 as a workshop co-directed by bassist Clyde Reed. The first Sunday, seven people came. Each Sunday a few more players people would show up, so Mr. Ranger brought in some of his charts and began writing for the group. “I’ve always been a writer”, he says, “but I never had a chance to write for such a large group. I call it an Orchestra, because then it’s seen as serious.”

This is definitely a serious endeavour, judging by the caliber of the musicians. Some of the players are known as “inside” players, meaning they favor structures. Others are known as “outside” players. Robin Shier (trumpet) is known as a musician who can read impossibly difficult charts and never make a mistake. Bruce Freedman (tenor sax) is known for fiery passion. Ron Samworth (guitar) is an expert at soundscapes. There are younger players too, some classically trained and new to jazz, like flautist Suzanne DuPlessis and soprano saxophonist/clarinetist Francois Houle.

When asked how he picks his musicians for Jade, Mr. Ranger states in his simple style, “They just come; if they’re good players, and want to stay in the band, they can stay. There’s no fighting in the Orchestra. It’s name is Jade, and that means it’s peaceful.”

If one wants to play Ranger music, one has to come to the rehearsals and work hard. This Orchestra is a work of love as well as a chance to work with one of the most musically respected players in all of jazz. Operating a 19 piece ensemble is expensive, and there’s no money yet to pay for rehearsals.

A name is mentioned, how did you choose her? Mr. Ranger shakes his head, as if the question is inane. “She does her job; she knows her part,” he says. His words are a compliment. They are a statement of fact meaning she can play the music the way it is meant to be played.

Another name is mentioned, how did you pick him? Mr. Ranger says “Yeah, the crazy guy.” Mr. Ranger is 50 years old, and while he is not a be-bopper, some of his English-language slang dates from that period. “Crazy” is his highest compliment.

The fact is Mr. Ranger knows exactly what he wants from the musicians because the music is his own. He has been in the music business a long time. He’s seen all its shades, from the jive to the sublime. Jive will not cut it with Mr. Ranger, but neither does one have to be a master musician. He writes what he hears inside himself, and then assigns the part to the players who can express it musically.

The player who solos on a Ranger chart needs a few other qualities besides the ability to play music. The musician needs fortitude and a lot of courage. Mr. Ranger is a leader who expects from others exactly the same musical thing he expects of himself. He expects them to play everything they are capable of all the time. Why compromise when it comes to making beauty?

The player who solos on a Ranger chart needs a few other qualities besides the ability to play music. The musician needs fortitude and a lot of courage. Mr. Ranger is a leader who expects from others exactly the same musical thing he expects of himself. He expects them to play everything they are capable of all the time. Why compromise when it comes to making beauty?

Bruce Freedman puts it this way, “If you’re not intimidated by playing with Claude, then your own music is going to be heavier with him behind you.”

Francois Houle related one of his experiences. “You have to play your ass off with Claude. My first time soloing with Claude was just an average jazz solo, but I had never gone that far before. He was talking to me through the drums twenty times faster than I could hear it. I was so dizzy at the end of the solo that I had to sit down!”

Friday, June 1, 1990, the Glass Slipper. The Slipper is packed with moms and dads, sisters, brothers, a picnic of relations come to hear sons, daughters and siblings play exciting music. The jazz gang is there to get a taste of the power of the big band in the intimate atmosphere this low-roofed club offers. Jade is ready to roll.

Claude Ranger calls in “Feu Vert” (Green Light). The tune is about being in a car stopped at a red light. Mr. Ranger instructs the soloists, “You’re the driver. When the light turns green, you drive away any way you want.”

The conductor, sitting at his kit, calls down the Orchestra. In this section, its just the drummer and the baritone saxophonist, Daniel Kane. The light turns green, and Kane hammers the pedal to the floor, a 1969 Chevy Impala loaded with a 451 motor, burning rubber at Raceway Park. The speedometer has no place to go, for the solo started at maximum revolutions. Suddenly Mr. Ranger drops out, and Kane hurtles down the highway alone as the drummer takes a swig of Molson’s Canadian and lights up another cigarette. Kane, having said his piece, slams on the brakes and screeches to a halt.

The audience is ready to burst into applause at the audacity of the solo. But Mr. Ranger, non-chalant, beats the audience to the punch. He lifts his left hand, circles his drum stick in a forward motion, and softly instructs, “Go; go!”

Green light! Kane is off again, alone, no accompaniment, screeching through hair-pin turns, jumping the gap of a draw bridge even as it opens to let a boat through. Sweat is pouring off his face, his eyes are bulging, chops on fire. Red light! Again the brakes, more rubber streaks on the highway.

There’s a brief pause, the band waiting for instructions. Claude Ranger knows how to build tension and expectations. The conductor again waves the magic wand. Kane has an incredulous look on his face as Claude Ranger again softly instructs, “Go!”

Feu Vert! Kane is known as a hard blower. The bores of the baritone saxophone are big like a cannon. The lungs have to push a massive volume of air to make music, and Kane is almost hyper-ventilating from the exertion. Claude Ranger is testing the saxophonist’s limits. Kane strains, summoning resources, finding a second wind, a Rocket 88 to musical heaven. Red light! The brake pedal goes to the floor, the last millimeters of asbestos shearing off the pads, metal screaming on metal, the radiator steaming, the burnt-out hulk careening to a stop. There’s thunderous applause from the audience, awe-struck grins on the faces of the musicians, blood on Daniel Kane’s reed. Claude Ranger waves his sticks and counts the Jade Orchestra into the next section. Soon another lucky soul will soon get the green light.

“I’m a changed man in 1990,” said Mr. Ranger when we talked in his apartment . He has regained his health since moving here from Toronto in 1986. “You can’t breathe in that city,” he says referring to the chemical and artistic atmosphere of that city. He loves the rain in Vancouver. “The sound of the rain helps me write. You know, I went to New York. The music came out there, but I had to get back to Vancouver because it’s so peaceful.” He speaks to me a bit about the misery of pollution and war, but then shifts right back to his music.

He has dedicated his next two years to writing his ultimate expression on humanity, Stars In Tears, a nine movement suite. To quote from his program, “The Stars are the Wise Ones. They see humanity at a loss. They are in tears.” The Wise Ones send an emissary to earth with a message “to encourage beauty and harmony among people.” A visionary man, Mr. Ranger has titled some of the movements with names like: ‘Ballad to the Stars,’ ‘Flowers of the Spirit,’ ‘Entre Ciel et Terre”. The final movement is ‘Valse aux Etoiles (Waltz Majestic).’

The projected instrumentation is 19 pieces, the same size as the current Jade Orchestra. Mr. Ranger envisions bringing the final version to different Canadian cities, perhaps with his own rhythm section, to be played by the musicians from the areas he visits.

Although he studied harmony and arrangement in the beginning of his musical career, this project is no simple task. Claude Ranger is the type of person who writes a piece but can’t shake himself loose from it. He is impelled by his own nature to continually perfect the possibilities of the music. He says, “Arranging is not tough; making a decision is tough. If I could just leave it alone! But it has to sound right, and I hear new things every day.”

There is a modal quality to his compositional style. For example, ‘Wood Nymph’ uses the Aeolian and Phrygian authentic church modes, lending the piece its impressionistic, pastel, and emotional qualities. He usually goes for the open position of the chord, searching for the strongest possible voicing.

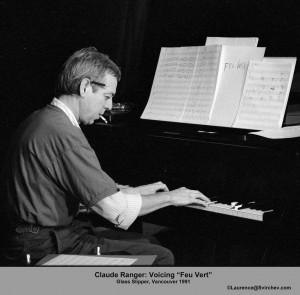

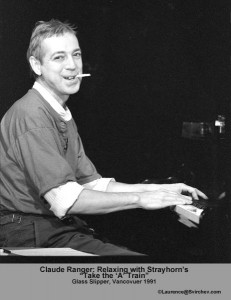

January 6, 1990, the Glass Slipper: Claude Ranger has been stuck on a section for several days. He usually works at home in a tiny room filled with plants, a little white pussycat, and a Fender Rhodes electric piano. But the room is too small to take a portrait of Claude Ranger working on his charts unless I photograph through the window, balancing myself out on the eave and the roof gutter. That is not too appealing, so we head to the Glass Slipper for a composition-photography session.

Mr. Ranger likes to compose hearing the electric sound of the Fender Rhodes, but the baby grand at the Slipper gives him a different quality of sound to work with. When he finds the sound he wants, the left hand holds the chord while the right hand notates the chart. After a few minutes of running through the voicing of the tuba section of ‘Wood Nymph’, Claude Ranger becomes ecstatic. Within two hours, he solves a slew of problems. Quebecois eyes are smiling, even though the mouth is still a bit set.

At the end of the session, I ask why he doesn’t use a piano in the band. He says, “The piano can do everything, so it should be played by itself. If I were able to play piano, I wouldn’t be a drummer.” He then demonstrates the exuberant introduction to the most famous of all jazz compositions, Billy Strayhorn’s ‘Take the A Train.’ “Duke Ellington conducted from the piano. He’d play the introduction like this and let the band do the rest!”

Mr. Ranger’s version swings like the Notre Dame Cathedral clappers. The pianist is smiling, a goofy boyish grin on his face. But what is remarkable is the classical, pianistically correct positioning of his beautiful forearms, wrists, and hands. Although Mr. Ranger’s skin is milk-white, the music and the hands are reminiscent of 1920’s Harlem stride pianists like James P. Johnson, players who could say anything from the piano, but never played a classical gig in their lives.

Mr. Ranger’s version swings like the Notre Dame Cathedral clappers. The pianist is smiling, a goofy boyish grin on his face. But what is remarkable is the classical, pianistically correct positioning of his beautiful forearms, wrists, and hands. Although Mr. Ranger’s skin is milk-white, the music and the hands are reminiscent of 1920’s Harlem stride pianists like James P. Johnson, players who could say anything from the piano, but never played a classical gig in their lives.

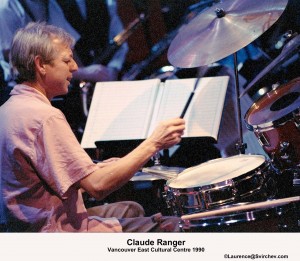

If one cuts through the smoke and watches Claude Ranger play the kit, there are several things to observe closely. You can tell that the music is going well for him when his eyes are closed. He rarely watches other musicians, interacting only musically with them. If the music is really going well, a small smile of contentment appears. The facial muscles are smooth and relaxed, as are the shoulders. The torso is held straight, the elbows a good distance out from the trunk.

His drumming motion is concentrated in the wrists and ankles. All the rest of his body is a anchor for those four pivot points. From the physiological call of view, his drum posture is a textbook example of how to get the most music from the modern drum kit. From the ergonomic point of view, he is completely efficient.

“Oh yeah, I’ve practiced,” he says. “I’ve practiced so much. One of the thing I did was practice with books under my arms.” That explains how the elbows are always held naturally out from the body, allowing for the natural shift from any one component of the kit to the others. It also helps explain the endurance, strength, and the huge sound this small-statured man gets from his small kit.

He also did things like practice with only the left arm and foot going, forcing himself to keep the other limbs completely still. He’d practice various combinations of one, two, three, and four limbs going at different meters. That helps explain the fluidity and the beer-cigarette tricks everyone is so amazed at.

Clyde Reed had this to say about Mr. Ranger’s drumming: “Some players have the music structure down pat, but they don’t have much emotional content. Others have the emotional content, but they can’t keep the structure straight. Claude is one of the few guys who has the cold, mathematical sub-divisions of the music down solid. But at the same time he’s got a burning heart in terms of emotional content. And if you want to lose someone in the sub-divisions of time, just turn Claude loose.”

That very thing happened on Sunday, March 4, 1990 at the Tom Lee Music Hall during a Barry Harris Trio gig. Harris is the venerable pianist, the bassist for the gig was Chuck Israels, and Claude Ranger was subbing. Israels, moody during the sound check, was clearly having trouble keeping his time straight. At one point in the second set of the concert, he shot a dirty look at the Claude Ranger and imperially commanded: “Play louder!”. Claude Ranger was playing with his eyes wide open that night, an equally clear sign that he was not happy with the way the music was proceeding. At the command, he dropped the brushes, picked up his sticks, doubled-crashed the ride cymbals, triple whammied the bass drum so loud that Israels jumped about six inches in the air. Mr. Ranger then accelerated at warp speed through the sub-divisions of time. The bass player was completely flummoxed, but the drummer came down on the one every time. Barry Harris, bemused and gentle-manly, played the wise-man and dropped out of the proceedings.

It began to look like one of those Ranger stories from his Toronto and Montreal days. But is attitude has mellowed, and in spite of the public insult, he stayed at the kit. After all, he became a new man in 1990. He’s got new vistas in front of him, an ultimate statement to make. He strikes people as more content, a self-assured man who knows his own capacities.

There are plenty of stories about Claude Ranger like the ones told in this profile. That is why, when he is introduced on the bandstand, the master of ceremonies usually says, “Ladies and Gentlemen, the legendary Claude Ranger!”

There are plenty of stories about Claude Ranger like the ones told in this profile. That is why, when he is introduced on the bandstand, the master of ceremonies usually says, “Ladies and Gentlemen, the legendary Claude Ranger!”

Originally published in Step Magazine, Vancouver, BC, 1991, photos added 2012.

Author’s 2010-12 Note: Claude Ranger has disappeared from the scene. If anyone knows his whereabouts, please contact Misterioso.