by: George E. Lewis

If you want to see a telling face of the Globe Unity Orchestra, watch the opening moments of Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s 2006 film, Das Leben der Anderen, about the dislocations of community under the Stasi-surveilled Deutsche Demokratische Republik (GDR). Notice the portrayal of a typical club date of the period, dedicated to the security of the State, with a congenial saxophonist in a typical German cap heading up a dance band dubbed the “Manfred-Ludwig-Sextet.”

If you want to see a telling face of the Globe Unity Orchestra, watch the opening moments of Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s 2006 film, Das Leben der Anderen, about the dislocations of community under the Stasi-surveilled Deutsche Demokratische Republik (GDR). Notice the portrayal of a typical club date of the period, dedicated to the security of the State, with a congenial saxophonist in a typical German cap heading up a dance band dubbed the “Manfred-Ludwig-Sextet.”

But yes, Virginia, there really was a Manfred-Ludwig-Sextett in the GDR, and for me, the scene bristled with an irony perhaps unanticipated by the director, as I waited (in vain, unfortunately in this case) for the congenial fellow, Ernst-Ludwig “Luden” Petrowsky, to break out into the torrent of sound for which he became famous in the Globe Unity Orchestra – perhaps to provide a radical Kaputtspielen of both the easy sonic fictions of the film and a possible resistance to the East German state along the way.

I do find it difficult to imagine Oscar-winning directors believing so passionately in the power of experimental music to change lives – at least, that isn’t my experience of big-screen film. Perhaps, instead of a child, a computer could lead them; these days, as one Googled computer told me, “People who like Manfred-Ludwig-Sextett also like DJ Matsuoka.”

The machine had a point – the cultural climate in which European jazz after 1965 came to prominence featured new, musician-directed, networked structures of feeling. As the radical nature of the music gradually came to consciousness, the European record companies that recorded the first free jazz expressions on the continent – some of them local subsidiaries of US companies – gradually stopped calling. After all, the music itself had ceased to become a local subsidiary; beginning roughly in the mid-1960s, musicians were fashioning extensions and ironic revisions of American jazz styles into a self-conscious articulation of historical and cultural difference that opened new directions in late 20th-century musical experimentalism. At first, this new, specifically European style of “free jazz” built upon the innovations in form, sound, method, and expression advanced by Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, Cecil Taylor, John Coltrane, and other African-American musicians of the early 1960s. Later, the new European musicians were widely credited with having broken away from American stylistic directions and jazz signifiers. Borrowing from a critically important event in 19th-century American history, the end of chattel slavery, Joachim-Ernst Berendt, in a 1977 essay, called this declaration of difference and independence Die Emanzipation.

The machine had a point – the cultural climate in which European jazz after 1965 came to prominence featured new, musician-directed, networked structures of feeling. As the radical nature of the music gradually came to consciousness, the European record companies that recorded the first free jazz expressions on the continent – some of them local subsidiaries of US companies – gradually stopped calling. After all, the music itself had ceased to become a local subsidiary; beginning roughly in the mid-1960s, musicians were fashioning extensions and ironic revisions of American jazz styles into a self-conscious articulation of historical and cultural difference that opened new directions in late 20th-century musical experimentalism. At first, this new, specifically European style of “free jazz” built upon the innovations in form, sound, method, and expression advanced by Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, Cecil Taylor, John Coltrane, and other African-American musicians of the early 1960s. Later, the new European musicians were widely credited with having broken away from American stylistic directions and jazz signifiers. Borrowing from a critically important event in 19th-century American history, the end of chattel slavery, Joachim-Ernst Berendt, in a 1977 essay, called this declaration of difference and independence Die Emanzipation.

From Globe Unity’s very first concert in 1966, the total sonic experience of Europe – the local fairs and brass bands, the rarefied climates of Donaueschingen and Bayreuth, and the engagements with so many extra-European musical cultures – was giving rise to a new expression that put flight to the false division of intellectual and cultural labor heretofore known as “high and low culture.” The musicians even sought the far more ambitious coming-together of an imagined global community – a global unity – made more urgent than ever by the memories of the brutality of war come home that, as with Manfred Schoof, formed the background of the orchestra’s founders, an experience that no Americans born after the US Civil War ever endured in their own land.

Emanzipated Europeans found new ways to get their music before the public – first, by invading a social democratic system of cultural dissemination, formed in the first days of the Cold War, that was never meant to support music like theirs; and second, by recovering the strategy laid out in the old folk tale of the Little Red Hen: If no one will help me plant these seeds, then I will do it myself. Thus, the entire recorded legacy of European free jazz, free improvisation, or whatever one wishes to call this music, rests upon this edifice of self-determination.

In the wake of the independent activity of musicians – the ubiquitous personal record companies, the self-produced festivals, the self-financed tours, and the collectives, such as Freie Musik Produktion (FMP) and the Beroepsvereniging van Improviserende Musici (BIM) – a younger generation of producers, similarly Emanzipated by this strange new music, added an important new network for creative expression. But for the most part, the musicians own the means of their production, and many of their self-produced works, such as Globe Unity’s 1973 Live in Wuppertal, have been rendered classics with the passage of time.

In later years, European musicians found ways to reconnect with the African-American traditions that they loved. As Alex told me pointedly on my rookie tour with the Globe Unity of the 1980s, this was free jazz, not free improvisation – explicitly asserting his right to link with the jazz tradition (or indeed, any other) – in an imagined community of affinity and love that had evolved away from its origins in a politically and culturally necessary pan-Europeanism, a version of what Gayatri Spivak called “strategic essentialism.” Indeed, in a cosmopolitan experimentalist environment, where musical affinities overflow borders with alacrity, the work of Globe Unity and many others forces an inquiry into exactly who is being served by the too-easy conflation of sound and race. What reason is there, then, not to place Globe Unity in the African-American tradition as well as the European, if musical taxonomies turn on sound and not simply ethnicity and race? Who is to doubt Peter Brötzmann’s 1968 declaration to a Jazz Podium interviewer: “I am definitely drawing on things that King Oliver did fifty years ago.”

During the rehearsal week for this recording, the writer Maxi Sickert published an article in Die Zeit that reminded the musicians of one of the signal events in the recent history of the Globe Unity Orchestra, the 1987 performance of the Globe Unity Orchestra at the Chicago Jazz Festival, part of our first-ever American tour. As Sickert reminded her readers:

“In the eighties, the Globe Unity Orchestra traveled around the world for the Goethe Institute, as ambassadors of German culture. Listening habits had changed; free jazz had found an audience. Only outside of Europe did listeners leave the concerts in droves, with their hands over their ears or, as in Chicago in 1987, waving white flags as symbols of surrender in response to all that cawing, tooting, hammering, and squeaking that was supposed to be music. They were not used to free jazz from Europe.”

To be sure, the old canard about the supposed lack of audience for free music, so carefully cherished in sectors of the 1980s American jazz community and widely touted by their media boosters, had been superseded in 1980s Europe by the experience of enthusiastic audiences for live concerts. After all, this was their music. In contrast, the Chicago concert, in which I participated, was indeed quizzically received by a fair portion of my hometown festival audience, many of whom were undoubtedly experiencing European free improvisation for the first time. And of course, we all remembered the white flags; from my stage vantage point I could see people in the audience with whom I’d grown up who liked the music, and others who were clearly wondering what I was doing onstage with those people.

All well and good – as an experimental artist, one lives with ambivalence. But what did my hometown audience hear? I want to explore this by way of a talk I heard in Berlin in 2007 by the philosopher Arnold Davidson on the Aristotelian ethics of the mentoring relationship between philosopher and student. Using the work of Cecil Taylor and Steve Lacy to explore this complex relationship of mutual learning between a learner and an exemplar, Davidson made it plain to us, in terms that every creative musician understands about the nature of exemplarity: “It is clear that nobody can learn anything from an imitator.”

Except, perhaps, about the futility and frustration within the collective consciousness that follows from an imprisoning reliance on imitation. Indeed, this was part of von Donners-marck’s point in his film. Human beings both crave and fear those who dare to be themselves in public, and one cannot deny that for those who uncover the extreme uneasiness engendered by this opposition of fear and craving, there is a price to be paid – but also, possibly, a redeeming, emancipating joy to be explored. And as Sickert noted in her article, our musical challenge to borders of consciousness was soon followed by the destruction of a Maurer that was always assumed to be permanent.

And to think it all started with what Alex called, in our rehearsals for this recording, “the famous single notes” – a structural element/method that became a distinguishing mark of a tradition of practice. I am very proud to be a part of this history, and even in the midst of mourning the passing of the great Paul Rutherford – whose word to the wise in 1976 (about, of all things, trombone mouthpieces) changed the way I think about sound production forever – I want to celebrate, along with you, the listener, the fortieth anniversary of this unique, wonderful ensemble.

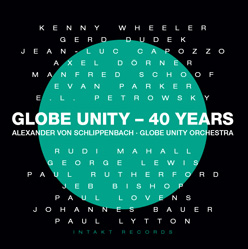

Editor’s Note: This essay was written by George E. Lewis, a member of the Globe Unity Orchestra, as the liner notes to Globe Unity – 40 Years. (Intakt CD 133 / 2007). The accompanying photos were taken by Laurence Svirchev at the 40th Anniversary concert during the 2006 Berlin Jazz Festival. The band photo with Rudi Mahall and Johannes Bauer soloing appears in the in the CD booklet.