Words and Photography ©Laurence Svirchev

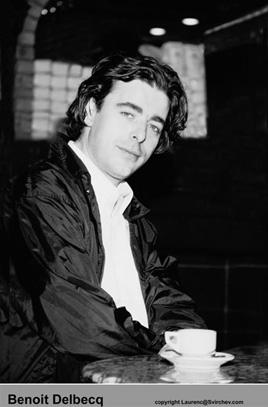

On a Monday morning François Houle, Michael Moore, and I met in the lobby of the Hôtel Compostelle. We crossed the rue du roi du Sicilie and went into a little bar for café and croissants. It took 15 minutes in Parisian rush-hour traffic to find a taxi to the suburb of Alfortville. The rest of the cast, percussionist Steve Argüelles, bassist Jean-Jacques Avenel, and composer/pianist Benoît Delbecq, were already in the studio. A good thing, for it had taken had taken Delbecq over a year and a half to get the other four musicians, each from different countries, into the same city on concurrent days.

On a Monday morning François Houle, Michael Moore, and I met in the lobby of the Hôtel Compostelle. We crossed the rue du roi du Sicilie and went into a little bar for café and croissants. It took 15 minutes in Parisian rush-hour traffic to find a taxi to the suburb of Alfortville. The rest of the cast, percussionist Steve Argüelles, bassist Jean-Jacques Avenel, and composer/pianist Benoît Delbecq, were already in the studio. A good thing, for it had taken had taken Delbecq over a year and a half to get the other four musicians, each from different countries, into the same city on concurrent days.

Relaxed, jovial, and still hungry, we marched through the neighborhood until a pastry shop attracted us. The bags containing our goodies were marked with grease stains by the time we arrived at a studio nascent with sunshine. Studios are too often shrouded in concrete-block ambiance, no windows in sight. But the natural light shimmering through the translucent dome of the Muse en Circuit carried an unexpected atmospheric warmth, making it an excellent place to record Delbecq’s dreamy music.

Filled with almond paste and sugar, the horn players goofed around while Argüelles set up his drum kit and electronics, Avenel plugged in, and the piano tuner went about his touching, tightening, loosening, and vacuuming tasks. The tuner seemed to have an awkward relationship with space, but then his eyes could not register the same electromagnetic spectrum that the rest of us in the room could. White cane and all, he was accepted as a confrere, a brother of unusual skill in making the master instrument ring true to western temperament. Now all that was left was for Delbecq to place his carved wooden pegs, tiny tree branches and rubber wedges between piano strings, Thierry Balasse to set the sound levels, to rehearse the ensemble through the intricacies of the compositions, and for artistry to take final command.

Delbecq had told me during an interview at the 1998 Jazz Happening in Tampere, Finland, “The more simple the music, the more complex it becomes when viewed through a microscope.” Musicians often verbally confound listening with visual aptitude (after all, they “hear” colors) but Delbecq’s statement nicely sums up his personalized approach to music-making. The journalist in me saw the music-making process differently, a wild oscillation between capriciousness and solemnity. The horn guys provided the hilarity, the rhythm section the sobriety. The center of gravity between this yawing was Delbecq himself, rock steady in his convictions after more than a year of thinking, organizing, and composing behind him.

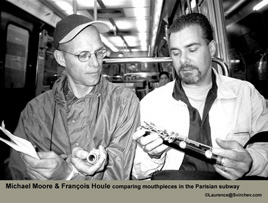

The appearance was that Moore and Houle had virtually no responsibilities except to blow. In the between times when they faced the microphones and actually did some work, their mirth alleviated the high specific gravity of the bassist and percussionist. Take Michael Moore, playing three reed instruments: he is one of those genius players capable of isolating a purity of color, or of rendering a hue to an intensity as sublimely complex and as rarely observed as an alpenglow.

An American who has lived in Amsterdam forever, his humor is as infinitely cheery as the lilt on the hip lids he sports. But behind the smile perpetually lingers artistic surprise. During the rehearsal of Polders, Moore pointed to the chart and asked Delbecq, “Do you want me improvise around these notes? “Benoît replied, “Yeah, it’s like a little can of notes.” Moore’s instantaneous reply was a vocal modulation that curved the context from a container to a descendant of Genghis: ”Is that a can of notes, or a Khan of notes?”

If Moore’s droll personality were to be challenged within the ensemble, it could only be by Steve Argüelles. The percussionist can’t help but be viewed as fastidious. Slender, quietly observant, and adroitly intelligent, he frequently abstains from the ravenous gusto of post-gig gluttony and bravado many performing artists are known for.

If Moore’s droll personality were to be challenged within the ensemble, it could only be by Steve Argüelles. The percussionist can’t help but be viewed as fastidious. Slender, quietly observant, and adroitly intelligent, he frequently abstains from the ravenous gusto of post-gig gluttony and bravado many performing artists are known for.

Argüelles’ fussiness is his own pre-condition of artistry, meticulous craftsmanship. While he ranks in the forefront of improvisers who use combinations of electronic and acoustical instruments, he does not play by any rules but his own. Whereas most formulate their arcane art in electronic laboratories, Argüelles exercises his alchemic stealth extemporaneously by recording the band (including himself) live. In mid- or end-song, he plays the recorded material back using Sherman and delay units to alter pitch, bend notes, and change the velocity or pulse of the music. His unique skill arouses dissonant associations with the music that has been played only minutes previously. This twisting of collective memory mutates the interaction among the players, and like a deus-ex-machina,he alters the consequent course of song.

Then there was the perplexed partner. Jean-Jacques Avenel is the extraordinary bassist of Swiss origin. Virtually unknown in the United States, his name typically provokes remembrance when his association with Steve Lacy is mentioned. In the studio, Jean-Jacques spent much of his time putting his glasses on to read the charts, or taking his glasses off before putting his hands on the bass to practice his parts.

Occasionally he would humorously make his self-perceived fragile relationship to the music known. When Delbecq was explaining Polders, he said, “It’s like a trapeze act where two people meet in mid-air.” Jean-Jacques’ repartee was, “Then we better practice, or it could get dangerous.” But when it came to the time to record, JJ’s judicious investigation of the composition led to dramatic accelerations and decelerations in the opening bass solo. Delighted and amazed, Delbecq leaned over and whispered to me, “There is no greater privilege in life than to play with guys like Jean-Jacques!”

Avenel had an anchor sound and a rhythmic approach Delbecq wanted for this recording. One of the compositions was Bogalan. The title comes from an African textile form in which squares of woven fabric are patched together randomly. “Jean-Jacques,” said Delbecq, “has a strong African influence in his playing. By transcribing his recorded solos, I learned how to make his approach to the bass work with my music. Our knowledge bases intermingle. For example, African music makes use of illusions of speed. Ligeti through his studies has done the same thing.”

Delbecq does not come straight from the American school of jazz. His extra-musical studies include textile art, theater, architecture, the mathematics of imaginary numbers and the rhythms of foreign languages. He goes so far as to say, “I get more nourishment from the other arts and life itself than from music.” His musical influences are equally catholic. He has studied the European new music, African pygmy rhythms, and Afro-American-inspired music. He says, “Steve Lacy was my call to music. Lacy is also the one who told me, ‘Follow your own path, but make sure you make enough money to pay the rent.’ After a lesson with Mal Waldron, the pianist told me I should never take gigs as a piano bar player, that it would ruin me as an improviser.”

While studying at the Banff School in his early twenties, the great theorist and composer George Russell bawled him out. “I couldn’t read very well and Russell said to me, ‘You fucking Frenchman! There are so many great French composers, and you can’t even read music!’ So I said to myself, ‘That kind of insult will never happen again’, and went to a conservatory to study.”

“I began to question how one hears and develops their own musical language and still manages to communicate with other musicians. I also was influenced by Ligeti’s scores and that helped me to put my finger on my real desire, to compose. Composing music is sacred event, a privileged moment of the imagination-life.”

Between takes of Within the Mean Time, Delbecq spoke into a µ-cassette recorder, “The composing happened over a long time, keeping notebooks on the road, thinking about the band, listening to music the guys had recorded. I first imagined shapes, then junctions between and among shapes. Then came vectors, movements, articulations. The last step was to write the notes sitting at a table, not at the piano. Each composition relates less to my playing than to elements that will catalyze the band to find a new way of playing.

“For example, Strange Loops starts with a written bass line. It is designed to be played physically, to create the investment of the player. It requires chops to play some of the difficult intervals and glissandos. The melody itself is little fragments of previouscompositions, my first composition written with the idea of cut-ups. These are directly related to the work with my poet friend Cadieux. Working with him gave me a kind of freedom. Before, I was thinking ‘one tune is one direction.’ Now I can make a tune go in one direction, but fill it with micro-directions. Like the micro-grooves in Ntshaks. I can go from one view, take another view, and go back the original view. That is getting close to literature. You know how Capote writes in Breakfast at Tiffany’s? He brings you to different layers of comprehension. And I like to have that feeling in my music.”

difficult intervals and glissandos. The melody itself is little fragments of previouscompositions, my first composition written with the idea of cut-ups. These are directly related to the work with my poet friend Cadieux. Working with him gave me a kind of freedom. Before, I was thinking ‘one tune is one direction.’ Now I can make a tune go in one direction, but fill it with micro-directions. Like the micro-grooves in Ntshaks. I can go from one view, take another view, and go back the original view. That is getting close to literature. You know how Capote writes in Breakfast at Tiffany’s? He brings you to different layers of comprehension. And I like to have that feeling in my music.”

And what role did François Houle have in the dynamic of this band? After a decade of listening to the hundreds of improvising musicians who have played in Vancouver, BC, I’ve formed the opinion that Houle is the outstanding clarinet virtuoso of improvised music resident in North America: his lexis comprises a substantial classical and new music vocabulary and his grammar surpasses the superlative in creating a contemporary musical literature.

Delbecq’s bizarre composition µ-turn is an eerie walk on a moonlit night across a highplain with hobgoblins, h’aints and other ghostly apparitions jumping out from every shadow. Unearthly sounds signalizing trepidation came from Houle whistling through the bore of a b-flat clarinet bereft of its mouthpiece. He often played through two clarinets simultaneously or broke down the clarinet’s sections, sounding the reed through a fore-shortened instrument. His solo on Polders demonstrated a requisite fragility required by the song. His musical intensity in the studio was unrelenting.

The Moore-Houle clarinet duo made quite a team for Delbecq, for his compositions now could have up to four wind instruments sounding simultaneously. Delbecq’s music is marked by a dream-like quality and one of the compositional techniques he used was for Houle and Moore to approach each other harmonically only to depart after brief consonance, a nice use of the musical device of tension-release.

After two days of recording, the Delbecq 5 packed up and went over to les Instants Chavirés, a Parisian jazz club. At sound check, a photographer from a philanthropic foundation did some shots of the band. She was all-professional and also rather cute: the boys in the band had no trouble giving her appropriate smiles while she opened and closed her aperture. The band had coalesced into consubstantial comity, the nervosity of the studio gone like yesterday’s clouds. They filled les Instants Chavirés with music from the recording as if they had been playing it on the road for years. The next day I left for assignments in Barcelona and Granada, confident that the next days’ session would yield one of 2000’s singularly superlative recordings.

Pursuit by the Delbecq 5 was issued on Songlines SGL1529-2, www.songlines.com/

This essay originally appeared in Planet Jazz, Montréal, Spring/Summer 2000.