©Laurence Svirchev

A host of individuals in the history of jazz have had a unique, instantly identifiable sound. Think of Louis Armstrong, Earl Hines, Coleman Hawkins, Johnny Hodges, Cecil Taylor, or Paul Desmond, and just as easily think of many more. But here’s a difference between an individual having a sound, and a group having the same. The Dave Brubeck Quartet, the Modern Jazz Quartet, the Basie and Ellington ensembles had that quality, and from there the naming gets more difficult. The changing aesthetics of the jazz business, the forceful personalities of its musicians, and its come-and-go economics all to easily lead to transient group dynamics, the Miles Davis Quintet being an example of a group that could not last.

A host of individuals in the history of jazz have had a unique, instantly identifiable sound. Think of Louis Armstrong, Earl Hines, Coleman Hawkins, Johnny Hodges, Cecil Taylor, or Paul Desmond, and just as easily think of many more. But here’s a difference between an individual having a sound, and a group having the same. The Dave Brubeck Quartet, the Modern Jazz Quartet, the Basie and Ellington ensembles had that quality, and from there the naming gets more difficult. The changing aesthetics of the jazz business, the forceful personalities of its musicians, and its come-and-go economics all to easily lead to transient group dynamics, the Miles Davis Quintet being an example of a group that could not last.

In today’s world, the above mentioned conditions have become exacerbated. It is next to impossible to tour year after year as a collective. In response to these conditions, creative musicians like those in Kartet typically have many projects on the go at the same time. Yet maintaining a group that can convert collective, aesthetic strength into a lasting dynamic is entirely possible, as Kartet demonstrates on The Bay Window, their fifth since 1992.

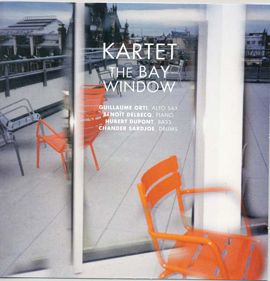

Kartet is made up of Guillaume Orti (alto sax), Benoît Delbecq (piano), Hubert Dupont (bass), and Chander Sardjoe (drums). The members are from France and that partially explains why they have been rarely heard in North America. Many of these appearances have been courtesy of the Vancouver International Jazz Festival.

Within Kartet, Chander Sardjoe doesn’t often pulsate into the foreground. He tends to understatement, the kind of flame-keeper who resides in the shadows. He frequently pops out of those shadows at the end point of a Kartet long-phrase when the splash of a ride cymbal sounds in the between-space bof the others’ playing. That sense of shadow is relative, for once submerged in Kartet’s music, it becomes clear that the sophistication of Sardjoe’s polyrhythmic drumming is one of the band’s signatures.

In contrast, Hubert Dupont occupies the foreground, the full-wood bass sound almost a lead instrument while retaining the more traditional role of rhythm’ning. His lead lines are clean and crisp, and have the beautiful quality of holding the last note in a phrase right into the decay zone, releasing it, and leaving a slice of silence before proceeding. His composition “D’Helices” (which could be rendered as “helix” or in motor terms as “propeller”) exemplifies this approach.

Guillaume Orti has a most distinctive voice on alto saxophone. His voice seems un-derived, as if he had first picked up a horn found in some desolate place, learned how to make sound, then music, and walked out of the desert and into a metropolis. The emotional state of his horn is heart-throbbingly high, as if exploring a new life forms during the beautiful illuminative times of sunrise and sunset.

Listen to his horn on his composition “Chrysalide/Imago.” Thierry Balasse’s close microphone technique puts the listener’s ear right inside the horn. Orti plays in slow motion with a sophisticated control of breath to the point where one can feel the horn’s metal cocoon vibrating molecular-level overtones. There is struggle portrayed in the music, something wrestling its way out of a physical constriction in order to take flight. Then begins a gradual acceleration, as if the thing breaking loose is gaining in muscularity. Delbecq and Dupont join in tandem matching bass note for bass note and Sardjoe slips in with his tricky rhythms and wonderfully-timed shimmering cymbals. Every being that gains flight must inevitably slow down as it loses its vital force. In nature, the small beings lose that force quickly when the weather turns chilly, and so it is with this song, an imago which fluttered beauty into the world for too-brief summer moments.

And then there is Delbecq. Misterioso has reviewed Delbecq’s music on two occasions (see the search function) so it is appropriate to let him speak for himself concerning Kartet’s arrangement of Thelonious Monk’s “Misterioso:”

“The bass and the piano’s left hand are actually playing the original melody, twice, quite slower than Monk’s recordings of it. That’s the form. The melody that comes on top, first and second time (with a three note fragment only played the second time). It includes elements from ‘Straight, No Chaser’ by Monk. Bar 9 is a quote from ‘Flakes’ by Steve Lacy, (agreed to by Irene Aebi [after Lacy’s passing]). The melody played by the sax and the right hand of the piano is build on a polyrhythm made of 10 against 4, which is what Chander articulates on drums, groove wise.”

Kartet is one of the few groups I have heard who can successfully take such liberties with a Monk composition. Their rendition renders the composition truly misterioso. (Incidentally, Steve Lacy told me in 1999, “Those Kartet guys, I’ve played with them. They write some hard music. It’s a bitch to keep up with them”).

If there is one thing vaguely disappointing in The Bay Window, it is that the compositions are brief and concise. This approach, while solidly documenting the compositions, makes me ache to hear again the stretched-out and improvisational music they play in concert.

Kartet is a contemporary band that has an advanced ensemble sound, an aesthetic they have been developing since their founding in 1990. Once heard, Kartet indelibly imprints on the aural centers their unique sound signature. Heard again and they will be instantly recognized. Kartet’s delicate agility makes their compositions feel relaxingly simple. They play a music in which space and time is dimensionally warped, yet the structures do not seem radical or jarring. On the contrary, they seduce the listener into believing that what is paranormal is normal. Kartet has a quality that the Andalusians call duende, a kind of indefinable combination passion, creativity, and risk. Their singularity is such that Kartet doesn’t remind the listener of any other band but Kartet.

Songlines SA 1560-2

Published September 2007