Words and Photography ©Laurence Svirchev

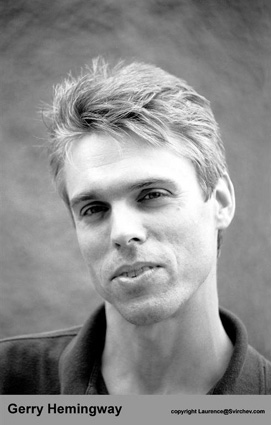

Gerry Hemingway has this smooth reserved body language. Sharply focused intelligence becomes obvious when one is close enough to observe his bright, penetrating eyes. When interested in a topic, he tilts his head inquisitively. His speech tones are of lower timbre and the velocity of words measured. In conversation his ideas are enunciated with architectural authority: his thinking on a given topic may range far afield but he always comes back, musician-like, to the “one.”

Gerry Hemingway has this smooth reserved body language. Sharply focused intelligence becomes obvious when one is close enough to observe his bright, penetrating eyes. When interested in a topic, he tilts his head inquisitively. His speech tones are of lower timbre and the velocity of words measured. In conversation his ideas are enunciated with architectural authority: his thinking on a given topic may range far afield but he always comes back, musician-like, to the “one.”

Although he eats heartily, his clothes drape loosely on him. He is clearly in good physical shape and it is difficult to decide if his slender frame is the result of a fast metabolism, the physical work he puts into drumming and road tours, or the mental effort required to collate a commanding knowledge of affairs musical, literary, philosophical, and social, of business, politics, and public education.

His ability to incisively and analytically think through a musical strategy is demonstrated when he discusses his duo concert last May with American pianist Cecil Taylor at Der Singel in Belgium. Hemingway explains that in Taylor’s drum-piano duos (specifically mentioning a collaboration with Max Roach) he has noticed Taylor and his co-musician doing what each does best but not necessarily playing off each other’s ideas and directly interacting. “I hear these concerts as a coexistence of ideas; some interesting things happen from these juxtapositions. But that is not the kind of player I am. I’m a listener, always inside and sensitive to whatever else is in the audio field.”

Perhaps some musicians go their own direction because they cannot unite with, understand, or bend the will of the shamanistic Taylor. Or perhaps they just cannot keep up with the dynamics of Taylor’s aggressive thought process. Hemingway, on the other hand, actively sought to explore an aspect of Taylor’s music, his sense of dance. “Cecil has spent a great deal of his life around professional ballet dancers. I always felt his phrasing has a real sense of how a dancer moves through space. The beginnings and ends of phrases have these special nuances, flourishes, and ways of coming to a point that are particular to the way ballet is often constructed. So I wanted to make a connection with that kind of phrasing.

“I think it happened, even more than I expected. I found myself playing a lot more marimba and vibraphone that I thought I would. The music we produced was far more transparent than I expected. There were periods of great density and energy, but I relished the moments when there was actual harmonic interplay and a sense of playfulness in reacting to each other.”

Hemingway’s reference to “harmonic interplay” is bang on. Taylor, of course, is renowned for his ability to relentlessly percuss the pianoforte (in this case a Bosendorfer with an extra half-octave at the bass-end) and make the instrument ring. By stressing the marimba and vibraphone, Hemingway incandesced his own sound. He thereby made a music that came to harmonic terms with Taylor’s aggressive piano-resonance. More importantly, Hemingway’s attack enhanced the overall musicality of the event. It was especially when Hemingway introduced instruments whose sound decays less rapidly than drum heads that one could feel Taylor concede his relentless momentum. The dancing-musicians seemed to lock eyes, change their sense of time, and launch themselves together- through space.

Hemingway is of course no stranger to the challenging affairs of improvisation. He spent many years in the crucible of Anthony Braxton’s music, their pianistic partner the formidably percussive Marilyn Crispell. At the 1999 duMaurier International Jazz Festival Vancouver, he teamed up with bassist William Parker and pianist Paul Plimley for a one-off improvisation that was a delight of the festival. He also has a longstanding improvisory association with pianist Georg Graewe and cellist Ernst Reijseger.

But Hemingway does not by any means confine himself to the work of spontaneous improvisation. His discography demonstrates a diversity of output, the staples of his road and recording work being his quartet, the quintet, and the collective trio BassDrumBone (with Mark Helias and Ray Anderson). Then there are the “oddball” self-assignments like solo and chamber works, and the enigmatic Thirteen Ways.

Thirteen Ways is Fred Hersch on piano, Michael Moore on reeds, and Hemingway. Like many of his musical associations, is Hemingway’s recent collaboration with Hersch and Moore has friendship and musical roots from his New Haven days (1972-79). The name of the group refers to the Wallace Stevens poem Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird. The group not a regularly traveling group, having appeared once at New York’s Knitting Factory when the album was recorded in 1995. They played two concerts at the Vancouver festival this year, leaving listeners craving for more.

Thirteen Ways plays a music that is spare, romantic, and beautiful, rare phenomena in art today. The touch of hands and blow of breath is light and subtle. It is a music that focuses the inner vision to sharpness, compels the ear adjust to intervals of nuance and silence. It impels the listener to breathe softly. The title track is a series of solos, duos, and trios, each section abstract and allusive.

Hemingway’s self description of “being sensitive to whatever else is in the audio field” can easily be put to the test in the low intensity atmosphere of the sounds of a bird’s wings, a sun-filled back-country town in Portugal, and the Hemingway-Moore duet,Steel and Clarinet. Hemingway is no bawd to euphony but listen to on the title track to his own Wallace-like inflections and innuendos, each as mysterious and elusive as a Japanese haiku.

Hemingway’s quintet and quartet, on the other hand, are often high intensity affairs. The drums and other percussion instruments are heard in the context of the complex and blowing sonic field surrounding them. He is certainly as schooled in percussion technique as anyone in jazz and improvised music, often felt more than heard among the maelstrom of sounds produced by Wolter Wierbos or Robin Eubanks, Ernst Reijseger, Michael Moore or Ellery Eskelin, and Mark Dresser. Anyone who has seen Hemingway playing knows he has a distinctive percussion style. But what are the qualities of his distinctive sound and how to get at them through the listening process?

Listening to Thirteen Ways and the Quintet suggest that Hemingway’s instrumental attack is kin to chapter changes, paragraph indentations, and punctuation that signalize coherence within a literary piece. Hemingway is often photographed in concert with his sticks frozen in mid-air. He is not a perpetual motion drummer. Blurring sticks through ferocious attack is not the market from which he draws his entire stock.

The period between strokes can be as important to rendering of the music as the intensity, placement, and velocity of the strokes. Hemingway tends to percuss with well-defined strokes, skipping a beat and stroking again with different intensity in an off-meter way. He also tends to color his way across cymbals with tangent slashes of the brushes. Perhaps most importantly, he tends to house his statements on one section of the kit at a time. This kind of sectioning breaks up the rhythm function that resides within every drummer, and allows him to state musical themes. He also surrounds himself with an array of other sound-makers, like Caribbean pan or glockenspiel to subtlety to color compositions.

intensity in an off-meter way. He also tends to color his way across cymbals with tangent slashes of the brushes. Perhaps most importantly, he tends to house his statements on one section of the kit at a time. This kind of sectioning breaks up the rhythm function that resides within every drummer, and allows him to state musical themes. He also surrounds himself with an array of other sound-makers, like Caribbean pan or glockenspiel to subtlety to color compositions.

(For a different take on his drumming listen to him power in ‘straight time” the Anthony Braxton Quartet’s version of John Coltrane’s “Impressions” closing out their 1992 Victoriaville, Québec concert. Or try his polyphonic solo during “On It” on his 1998 CD Johnny’s Corner Song).

The literary allusion to Hemingway’s instrumental technique also provides a gateway to both his compositional and improvisational mind-set. During a June 1999 interview in Vancouver, Canada, he stated:

“As an improviser, I’m generally speaking a formalist. If you want to characterize my work, I’m generally interested in forms, like sculpture, that make sense from top to bottom. I’m interested in how forms work in space, in the elegance of how they flow from one end to the other, in the three dimensional aspect, of how you can see backwards and forwards in a piece, that there is a reason to be at C just as there is a reason to be at A and B.

“at the same time, like the layering that occurs in literature, I’m interested in multiple layering in music, for different things to happen at different times. All those compositional things just mentioned I bring into my work in an open improvising situation. I’m looking at the same issues, just in real time. Even if others are less thinking along those lines, the way I work it tends to steer the music in that direction, just by virtue of ‘that’s who I am.” It is clear to me when I look at my work, that my syntheses of these elements has clarified over the years. And that is how it should be: the growth after the poverty is called maturity.”

Hemingway’s boldest composition may be the 1995 “Perfect World”, a musical outcome of what he has described in an interview with Keith McMullen as “an appetite for the unimaginable.” The twenty-two minute piece begins with a violent arco cascade by Mark Dresser lasting some eight seconds. After a five second silence, he repeats the cascade but doubles the length, then takes a period of silence and goes at it again. He builds the solo around a series of ascending lines. At the end of each of these lines, he dramatically plunges from the high end into the low end of the instrument’s range. Dresser’s attack allows him to express the instrument simultaneously in the nominal range of the cello and bass. The solo is dark and foreboding, each cycle ending with presentiment that a cataclysm is approaching. The time feel within each “µ-groove” (an expression used by French composer Benoît Delbecq) of Dresser’s solo is one of acceleration ended abruptly with a slash at the strings. As the pulse builds, one feels an increasing nervosity and the listener may well ask when deliverance into a world of tranquility will arrive.

Release of tension is never close at hand in Gerry Hemingway’s perfect world; when at three minutes into the Dresser solo the band enters, the suspense is torqued that much tauter by framing Dresser’s compelling momentum with alternating and accelerating vamps from Wolter Wierbos (trombone) and Michael Moore (bass clarinet). Wierbos and Moore are not even close to playing harmoniously or in time with each other. Hemingway’s entrance at the same time adds to the edge as he pushes the rhythm.

And then as if by magic, the elements of stabilization become heard at the end of the fourth minute. Hemingway’s beat starts to become steady, the bass pulls its way out of the maelstrom and at 5:51 Michael Moore and Ernst Reijseger (cello) play a voiced, repetitive groove used as a transitory device leading into, at minute eight, Wolter Wierbos’ solo. The tension then begins to rise again. The song follows this pattern of long periods of high-voltage as each musician gets blowing space. “Perfect World” ends with Hemingway’s denouement drum solo, a train you wouldn’t want to stand in the way of.

“Perfect World” is remarkable for its ability to sustain and increase tension over long periods of time. Hemingway uses several compositional devices to enhance the suspense and these include acceleration and deceleration of rhythm, the simultaneous playing of different rhythms and pulses, and having each musician free to float and modulate among the various tempi. The elastic palette of the sound field keeps the listener off balance, rarely capable of finding the point of equilibrium. Hemingway’s perfect world seems to be a plastic, asymmetric, and turbulent place.

While the composition “Perfect World” seems to be a musical result of hurricanes, earthquakes, and volcanoes, “The Visiting Tank” (1999 CD, Chamber Works on the Tzadik label) is a musical commentary on the effects of that perverse human invention, war, on children. In our Vancouver interview, Gerry Hemingway spent a considerable amount of time elaborating on this new work. It was clearly very important to him, not only because he had just finished recording, but because he is a father who thinks a lot about children. Here are some excerpts from the conversation:

“I had imagery in mind, a sense of place, content and feeling dealing with the dichotomy of children and war. The notion was that there was a tank in a playground and the kids were playing on it as if it were a jungle gym, exploring their childhood, right in the physical context of this machinery of hatred and destruction. I imagined what it must be like to be in that environment, imagined the real images of real wars, the reality of children having to survive wars.

“I combined my own dreamlike kind of sonic imagery with writing for a string quartet to convey sounds that might draw us into such an atmosphere. I used different sounds that I thought gave it a sense of place, like a clock ticking the passage of time; or the sounds of not knowing, like the tick-tock of a time bomb. You know the tick-tock when it goes through the speakers, but the pitch is changing all the time, it floats around in the atmosphere of sound and is processed in different ways. The sounds of people screaming are there, although you might not recognize it as such. There is a sense of terror, as in a dream; it’s not real and you can’t touch it.

‘that’s the wonderful thing about electronics. You have this chance to be poetic with sound. If you are handy with this machinery, you can convey some pretty interesting things. In “The Visiting Tank” I used associative sound work, which is common with sampling, but I was using associations which were semi-literal. I did pick things that sort of resemble wartime atmosphere in a literal sense, but the sounds were transformed so much that they don’t hit you over the head, like dropping bombs. I wasn’t going for the obvious relationships.”

The composition is spooky, placing one in a twilight zone of uncertainty in one section; suggesting kid-stuff on monkey bars in another; military officiousness in a third, and with desperate sadness throughout. The music was written during a difficult period of his personal life. He said, “I’ve got a wide palette of interests, and I found my writing for the string quartet ended up being a bit like my writing for the quintet. There wasn’t a big division between the work with improvisers and non-improvisers. In fact the musical results resemble each other, which tells me that in my work there is some consistent thread that I’m interested in as a writer. To me the string quartet captures my life inside and hopefully it is compelling enough to others that it offers some insight.”

Hemingway recently moved his residence, one of the reasons being to ensure his son was in a school district where children could have access to arts education. He is a man filled with a deep humanitarianism and understanding of the human condition. He surrounds himself with some of the most important musicians of North America and Europe. The Chamber Works are just one example of the projects that he has been thinking on for years, but “I won’t write a stick of music until I have the gig, recording, or whatever.” He has one of the more impressive and wide-ranging discographies of contemporary American composers, yet it is next to impossible to find his CDs, even in major record stores. Better to buy direct from his web-site or at his gigs. He tours more regularly in Europe than in his home-land. And yet he does not desist from creating serious works.

Hemingway has been asked many times about his relationship to the music of Anthony Braxton. In his interview with Keith McMullen, he replied to a question about this influence by saying, “He gave assurance that my obsession with music has a human basis, and serves a vital purpose in sustaining life with meaning on this planet.” In Hemingway’s music one finds beauty, violence, struggle for existence, the poetry of abstraction, and the highest order of musicianship. Hemingway may not live in a perfect world, but he does have a Perfect World of his own.

Originally published in Signal to Noise, Burlington, VT. http://www.signaltonoisemagazine.org/ , November 29, 1999

Gerry Hemingway’s Web Site is a formidable resource, with articles, biography and complete discography: http://www.mindspring.com/~gerryhem/

The following recordings as leader and collaborator were used to research this article:

Gerry Hemingway Chamber Works

Tzadik 7052

1999

Waltzes, Two-Steps, & Other Matters of the Heart

Gerry Hemingway Quintet, 1999

GM3043CD 1999

Perfect World

Gerry Hemingway Quintet, 1996

Random Acoustics RA 012

Duet with Cecil Taylor, unpublished concert tape provided by Gerry Hemingway

May 1999

De Singel, Antwerp, Belgium

Johnny’s Corner Song

Gerry Hemingway Quartet

1998

Auricle Records Aur-4

Thirteen Ways

Fred Hersch-Michael Moore-Gerry Hemingway

1997

GM3033CD

Slamadam

Gerry Hemingway Quintet, 1995

Random Acoustics RA 012

Graewe/Reijseger/Hemingway

The View from Points West, 1994

Music & Arts CD820

Anthony Braxton Quartet, twelve compositions

Oakland, Ca. 1993

Music & Arts CD835

Tambastics

Robert Dick-Mark Dresser-Gerry Hemingway-Denman Maroney

1992

Music &Arts CD704

Anthony Braxton Quartet

Victoriaville 1992

VICTOcd021

Gerry Hemingway Quartet

Down to the Wire, 1992

Hat ART CD 6121