Words & Photography ©Laurence Svirchev

A casual glance at the covers of glossy jazz magazines, a stroll through the aisles of any large CD store, or a squint at the fashion pages handily demonstrates the cult of handsome, competent, and female singers who tirelessly and tediously repeat the canon of 50-70 year old jazz standards. The glossy journalism that surrounds them celebrates their fine looks, calls the music jazz, and blatantly ignores the legions of far more accomplished artists who have set superior standards of challenging creativity.

A casual glance at the covers of glossy jazz magazines, a stroll through the aisles of any large CD store, or a squint at the fashion pages handily demonstrates the cult of handsome, competent, and female singers who tirelessly and tediously repeat the canon of 50-70 year old jazz standards. The glossy journalism that surrounds them celebrates their fine looks, calls the music jazz, and blatantly ignores the legions of far more accomplished artists who have set superior standards of challenging creativity.

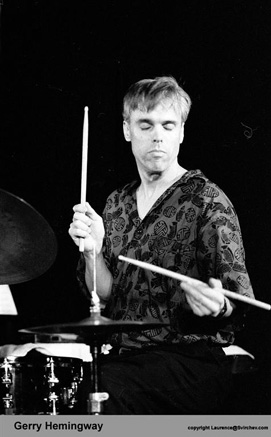

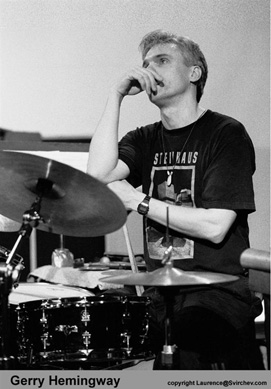

Enter Gerry Hemingway’s art-song project. Songs is a series of original lyrical and instrumental music incorporating elements of pop, new music, and improvisation. The songs unfold novella-like as real-life stories personalized from the ecstasy and agony of human emotion. The rhythms, harmonies, and melodies of each song are strikingly dissimilar and the improvisations that lace through each song make for evocative listening. Songs has the rawness of edgy pop music but the secret appeal is its complex musicality.

Erudite jazz listeners have for the most part placed their listening needs in the camp of the instrumentalist. Instrumental and lyric composition are usually considered related but distinct crafts (think Rogers and Hart or even Lieber and Stoller). In the jazz world, Steve Lacy is celebrated for his melodies and harmonies set to ancient and contemporary poetry. Betty Carter, Sheila Jordan and Louis Armstrong have been prominent for using their voices as instruments to create sounds beyond the realm of words. Musicians like Mingus had specific projects for the integration of poetry with music. But the number of jazz musicians who write both music and lyric is limited.

Furthermore, American jazz-song has been adsorbed generally alienated from the tradition of European art-song (a major exception being Brecht and Eisler). Hemingway, however, is an artist who has become familiar with the elements of many musics both through the musical company he keeps and the curiosity of his own listening habits. After a decade-plus working association with Anthony Braxton he went on to work with some of the important of European improvisers, such as Georg Graewe and Ernst Reijseger. His own quartet and quintet work employs the likes of Michael Moore, Ellery Eskelin, and Mark Dresser. He has a 25 year-old musical relationship with trombonist Ray Anderson and bassist Mark Helias and is a member of Anthony Davis Episteme Ensemble. Add to this his credits in electro-acoustic solo and chamber works, and now a Guggenheim fellowship out of which will compose a symphonic composition.

Furthermore, American jazz-song has been adsorbed generally alienated from the tradition of European art-song (a major exception being Brecht and Eisler). Hemingway, however, is an artist who has become familiar with the elements of many musics both through the musical company he keeps and the curiosity of his own listening habits. After a decade-plus working association with Anthony Braxton he went on to work with some of the important of European improvisers, such as Georg Graewe and Ernst Reijseger. His own quartet and quintet work employs the likes of Michael Moore, Ellery Eskelin, and Mark Dresser. He has a 25 year-old musical relationship with trombonist Ray Anderson and bassist Mark Helias and is a member of Anthony Davis Episteme Ensemble. Add to this his credits in electro-acoustic solo and chamber works, and now a Guggenheim fellowship out of which will compose a symphonic composition.

So why did he undertake the challenges of writing Songs? Hemingway seems to be challenged by the need to do somethingdifferent. He told me via the internet that “I felt the need to express ideas and feelings in a more direct medium than instrumental music. I also wanted to make a recording that was especially for my wife for very personal reasons. And I wanted to create a CD that would rival the popularity of the recordings that get listened to the most in our household. We share the enjoyment of an eclectic mix of gospel, pop, country, afro-pop, blues, jazz, lieder, afro-cuban, folk and bluegrass singers and songwriters. I was curious to see how I’d fare in such fast company.”

Hemingway is a man who reacts directly and emotionally to the world around him. Ask a question and you get a serious answer. He is candid about the sources of his lyrics, nonreticent in speaking about things ultra-personal: “There is a diversity of lyrical content on this recording and some of it is coming directly out of my life experience. When I started writing these songs I had a hit a bottom where I really had no choice but to confront some of the core issues of my life, a painful but worthwhile lifelong process and I know there are many who can relate to this journey. I also began to delve more deeply into what life was offering as lessons and writing these songs was a way to reflect on and process some of these experiences.

“The recording is dedicated to my wife Nancy, and indeed some of the lyric grew directly out of our ongoing dialogue and relationship. Her multi layered way of viewing things help stimulate my writing process. Sometimes a phrase, or a succinct metaphor would become the kernel for me to expand into a full song. Take the piece Time to Go. In general it’s about being able to distinguish between being adored for what you do, the image of who you are as a performer, and being your true self in an intimate relationship. There can be a tendency to favor work and fantasy over true intimacy.”

Time to Go is a rich act of connotation taking the listener through the two-world contrast that performers inhabit: the road, the music-making, and the applause, and on the other hand the intimate delicacies of home life. Hemingway asks rhetorically through lyric

“The glory we felt is over now, home sweet home is real but how?”

And he answers the question in the last stanza of this last cut, a denouement to the emotional odyssey from the rest of the CD:

“Here I am now, back in my world

making breakfast again, I am listening to Merle

I hope those I love, remember all of me

Not easy to be back// then leave”

Songs broadcasts over a wide range of settings, including the reference to a country musician called Haggard in the above-cited poetic excerpt. There is Succotash, a funky dance piece; In Your Arms, a sultry and suggestively sexy serenade about reunion. And there is Out of the Trees with its slow instrumental pace countered by high-velocity singing of the lyric. It is a song that explores the fine lines between staying in a relationship or leaving it:

“I dig into emptiness, looking for clues that lie

Between the forest of forgiveness and the wish to die”

Hemingway wisely employs a female voice, that of Lisa Sokolov. This aesthetic choice abstracts the songs’ emotions from his own experience. Of Sokolov he says, “I began working with her a few years ago in the context of her trio and quartet. She seemed to understand without any hesitation the process I was using for shaping these songs. Mostly I sang the song for her and did my best to convey with my limited vocal technique the melodic shape, phrasing, dynamic flow and emotional intent. She took the ball and ran with it, bringing the songs to life.”

from his own experience. Of Sokolov he says, “I began working with her a few years ago in the context of her trio and quartet. She seemed to understand without any hesitation the process I was using for shaping these songs. Mostly I sang the song for her and did my best to convey with my limited vocal technique the melodic shape, phrasing, dynamic flow and emotional intent. She took the ball and ran with it, bringing the songs to life.”

It took him two years to complete Songs, the longest he has taken on a project. He said, “I had never written a song and had no idea how to go about doing it. At first I simultaneously developed some musical sketches and some lyric, but they were not connected. For a long time I wrote only lyric, which I wrote with a musical sensibility particularly concerning the rhythmic phrasing and rhyming. The content of the lyric was always my guide. Eventually I was generating lyric from musical ideas and vice versa, which of course was when I had really found my groove with the project.”

Hemingway normally rehearses and records the material with all musicians present. The limited budget for Songs precluded the normal intimacy of the jazz recording process. So he went for the process well known to the pop world: record one musician at a time. He said, “This allowed me to incorporate more musicians than I might have otherwise by recording material when and wherever I met up with Wolter Wierbos, Thomas Lehn, and John Butcher. The rest of the material was recorded round the corner from where I live directly into my computer in a very small studio. As I worked with each musician we had the opportunity to delve more deeply than usual into the material we were working on in a relaxed and un-pressured way. That is not the case when the meter is ticking at a full fledged state of the art studio.”

The one composition that Sokolov does not sing on is the multiple-entendre story Anton. The song fictionalizes the last moments in the life of serial composer Anton Webern (1883-1945) who was shot by an American GI after the cessation of hostilities in WWII.

It opens with Hemingway’s electronically transformed voice chanting:

“Out for a cigarette, time to die

hushed beauty lost on a soldier’s scared eyes”

His lyric poetically summarizes what many musicians, as disparate in style as Webern himself and Count Basie, strive for in their music:

“Not one tone without meaning, nothing more, nothing less.”

Here is what Hemingway had to say about the musical aspects of the composition: “Putting aside the subtle reference to Nazi Germany in the audio poem that precedes the piece, the components of the piece are intentionally spare, not unlike the Webern’s style of expression. The bass line and on occasion the drum part offer continual aversion to expectation, which to some degree is one of the fundamental results of serial composing. Within this system Webern his voice. He also made use of additional methods to layer a hidden meaning in his choice of pitches which in the case of his “Five Pieces for Orchestra” made references to his mother. I sampled various snippets of this composition, using them as rhythmic chords, not unlike a guitar player might “comp” behind a soloist.“

Here is what Hemingway had to say about the musical aspects of the composition: “Putting aside the subtle reference to Nazi Germany in the audio poem that precedes the piece, the components of the piece are intentionally spare, not unlike the Webern’s style of expression. The bass line and on occasion the drum part offer continual aversion to expectation, which to some degree is one of the fundamental results of serial composing. Within this system Webern his voice. He also made use of additional methods to layer a hidden meaning in his choice of pitches which in the case of his “Five Pieces for Orchestra” made references to his mother. I sampled various snippets of this composition, using them as rhythmic chords, not unlike a guitar player might “comp” behind a soloist.“

The horn-instrumentalists are not often associated with singers and yet they magically weave their way through the compositions both supporting Sokolov and making independent improvisory statements at the same time. (Herb Robertson, Ellery Eskelin, Wolter Wierbos, and John Butcher) break completely with this model on Songs. Sokolov herself excels at extemporaneous singing.

Hemingway’s Songs breaks many of the stock patterns of the American song-book curiously passé. He has created a work that I predict will pass the test of time not only because the emotions he writes about are universal but mainly because of the innate musicality of the compositions and the music-making of his band mates.

This article was originally published in Coda, the Journal of Jazz and Improvised Music, September/October, 2003

Gerry Hemingway’s website is: http://www.mindspring.com/~gerryhem/