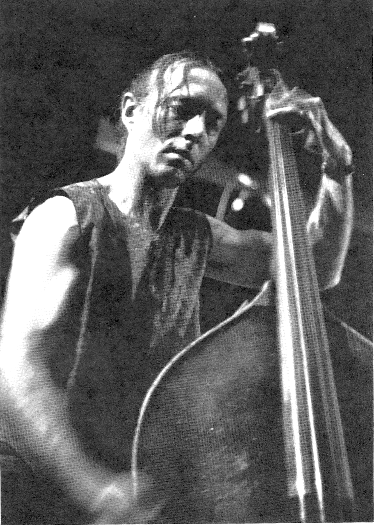

Interview & Photography ©Laurence Svirchev

Interview & Photography ©Laurence Svirchev

You never know what darkened comer Lisle Ellis music will strike from, what chops he will use to resonate never-before heard sounds from string and wood, or what instrumentation/choreography he will incorporate into a work. Lisle Ellis is a musical surprise attack, the ninja of the bass. Last November, Ellis performed his Archipelago solo at the Pitt Gallery in Vancouver. The pre-performance stage contained a double-bass suspended upside-down from the ceiling, a hand-lettered sign reading “Free James Brown”, Ellis’ birch-bark paintings and a bass case lay on the floor, a set of rattles strapped to the neck. The lights dimmed, and wood-block percussion as well as the rattles were heard. As the lights went up again, the eyes were attracted to the floor. The neck was shaking, and the rattle and body of the case was humping over the floor, like a rattle-snake.

Then Lisle Ellis, himself ensconced inside the case while its usual inhabitant hung from the ceiling, read a poem. When he emerged from his cocoon, he unstrung his bass, and began to play. In the middle of the performance, he cried out what James Brown must have been imploring the Parole Board: “Please, Please, Please”. The performance was a dark one, but as Ellis later said, “There are many different islands in the Archipelago.”

I conducted the following discussion with Lisle after the 1989 duMaurier International Jazz Festival. He had been through an intensive 3 weeks: duos with Paul Plimley and Pierre Tange, a trio with Marilyn Crispell and Roger Baird, jamming with the legendary drummer Claude Ranger, and leading the Freedom Force Ensemble, a group of Vancouver musicians put together by Ellis, himself originally from Vancouver.

Laurence Svirchev: I want to ask you about your musical and visual concepts. During the Freedom Force Ensemble, you had the musicians walking in up the aisle from the rear of the hall just breathing through their horns. It created a tremendous aura in the place – the audience was stunned by the silence. It was like the natural sound of the wind.

Lisle Ellis: The way we started that concert was something that I thought about, but also it’s something that I feel has been given to me at some point from what I’ve seen other people do. Like from watching Sun Ra a few weeks ago, seeing the Ellington orchestra, seeing Japanese Noh theatre.

There’s some kind of common ground to all of that which has nothing to do with jazz music or free jazz or whatever we want to call it. There’s these traditions that were here before we were here and we try and pick up on them. If you want to get to a certain place, you say “This is some kind of ritual function.” From the first step you have to have a “gong” to get everybody focused. It could be literally a gong -wham- or it could be something that has the same effect. There had to be something, and so it was the musicians’ breathing. Everybody was breathing, the audience was breathing. It’s like church. It helped the audience to focus on what was happening then, what was going to come next, and also to help the musicians prepare for what they had to do for their music.

If you don’t have a lot of rehearsal time, you don’t have a lot of time to get a feel for each individual and what they can do. We wanted to get a feeling that everybody’s together, a unification of the forces that are available with all that talent in the room and trying to utilize it in the best way possible.

LS: Part of your orchestration was two basses. You were leading and playing bass but Clyde Reed was also playing bass. How does two basses fit in with your music?

LE: Oh, just gives it more bottom. I also knew at times that I would have to put the bass down and do some pointing. It was great to have Clyde because he’s so experienced with this stuff. Clyde and I played two basses starting a dozen years ago.

LS: Later on in the evening you dropped the Ensemble format and did a quintet.Two basses, Dan Lapp on violin, Al Neill on piano, Roy Styffe on clarinet. No percussion?

LE:. I had the idea that at a certain point in the music, it might be nice just to have another color. We had all those saxophones and brass players with a rhythm section and a traditional rhythm section – piano, two basses, drums – and I just thought it would just be nice to do something completely different. It was a good change of pace. It solved an orchestrating problem for me. The chamber piece enabled the other musicians to very subtly move and take their positions around the room. When the chamber piece was over, they were already there in place for the next part.

LS: You had two dancers that evening, Natalie Jean and Beverly Harshenin. What kind of instructions did you give to them?

LE: Very little. I thought that basically they should do what they wanted to do. I had an idea for the beginning and I had an idea for the end and then what they did in the middle was up to themselves. They were fantastic. They added, as dancers always do, something very special. They created a focus for the musicians. In the ear is your centre of balance, so you know it makes so much sense that music and dance go together. We all need that, but dancers particularly need that to move properly, that equilibrium.

And right in there too is where the eardrum is too. So it’s all interconnected: the music and the dance. When a musician sees a dancer moving to the song that he or she is creating, it feeds back information and you actually see what you’re playing.

LS: Well it sure did have some feedback because during his solo, Bill Clark just dropped his horn and started dancing himself.

LE: That’s what happens, the whole thing escalates until – well that moment, what Bill did, was so fantastic. If you look at the traditions of the great orchestras of the world, I don’t mean just European classical but as well the great orchestras, like the Chinese orchestras, the Persian orchestras, it was always expected that the musicians could dance and that the dancers could play music and their positions were interchangeable. There was not so much of a separation. In Japanese Kabuki theatre the actor, it’s mostly male-dominated in that theatre situation, they play music, they’re trained as musicians, they’re trained as dancers, they’re trained as actors. There’s no separation. They don’t separate things out.

Westerners separate things. The western mind loves to divide and conquer all the time. We separate the rhythm from the melody and melody from harmony so we can really get down to the proton or the neutron or whatever. I’m not so much interested in separation as much as unifying things and bringing them together more, seeing the whole picture and keep talking about the Freedom Force Ensemble. There’s a powerful force here for people that are interested in this idea of unification, this idea of some kind of liberation through sound. The sound is the focus but there is also dance. It’s fantastic when you see that there’s a force here, and it’s a very contemporary thing.

You know you pulled out that T shirt about human rights with what just went down in China. Tiananmen Square with the one guy stopping the tanks. The shirt logo says “Stand Up for Human Rights.” Yeah, and this is another aspect of this idea of liberation. Our freedom, human rights, humanity is one thing. It’s made up of a lot of individuals but together we’re a force and the human spirit wants to fly, so to speak, wants to rise up and experience that light, that feeling of lightness, that we find in music and dance, climbing a mountain, being beside the ocean or whatever, and I guess these are the things that are important for me in music, and when I’m talking about music.

Bass players have an overview because bass players, you know, we’re the foundation. The American Indian, when they did their traditional rain dances, made the lowest note they could make and the lowest note was made on a big drum or by beating the earth with sticks or stomping on it. They beat the earth to make a bass note as just one big note. But it’s light as a feather and it floats up; that’s hot air, it rises. Bass notes are like big hot air notes and they’re very huge but they’ve got no weight they just rise up.

If you could see the notes of the piccolo or the violin, the highest notes, they’re like little lead balls. They’re like the rain, they’re very heavy, very dense. High notes are very dense. The American Indians know about the principles of this kind of thing. They made low notes that would go up and when the low notes go up, they stimulate the high notes, the raindrops, to come down.

Bass players, get a good overview in a traditional jazz rhythm section. The bass player listens to what the piano player, or to the guitarist, the chords that he’s playing down there, you’re getting the bottom note there, plus you’re interpreting the rhythm from the drums. So you’re acting as a. translator for everybody. You’re kind of telling the piano player where the rhythm of the drummer is at, and you’re telling the drummer what’s happening, where the next shift is going to come. And you’re communicating that to the front line, to the horn players and so a bass player is the intermediary.

You’re kind of keeping everybody cool, you’re like an octopus. I was never really that interested in being political, but when you make your sound it has an affect. You know there are implications in the music and when you start talking about freedom and human rights and liberation and what we were just saying, you know, that just the freedom to be able to look at the mountains and say “Wow, one day I’ll be free enough so that I can get up there and really one day I may be worthy enough to be at the top of that mountain.

When that went down at Tiananmen I heard that on the radio while driving out here from Montreal and hearing that first news report, I think the only thing that has moved me so much in my life was one time when I was a kid when Kennedy was shot. I thought about that a lot and I started thinking, “what am I doing with my music?”

Music is a sound, is a force. Sound goes out, it reaches people, it keeps traveling, it doesn’t stop just past the ear, you know. Things vibrate, walls, everything moves. We all know the story of Joshua and walls of Jericho, the trumpets. So, you know, it’s a force, and all of this is turning around in my mind. People were asking, “Well, what are you going to call this thing?”

I said, “Freedom Force” and for me it’s almost a political statement, the closest I’ve ever come to a political statement Because I know in my life the first sound that every attracted, the first sound that ever moved me was blues, and you know that was made by Black American musicians, but anybody can. There’s a similar quality if you listen to folk music from different parts of the world, there’s a certain quality oppressed human beings have when they make a sound, when they sing or when they play instruments, in oppressed people there’s a similar quality to be found.

The Freedom Force Ensemble was organized on pretty short notice, it got one of the largest jazz audiences in between the times when the recorded and international stars come into Vancouver. That says something about the ability of musicians in any locality to expand their audience and go beyond the hardcore jazz listeners. Sometimes it feels like we’re boxed because of musical labels – the folkies over here, and the jazzies over here, and classicals over there, and the rockers – there’s a wall between them and it would be nice to break that down.

I’m meeting more and more people that are less interested in jazz per se. I’m meeting more and more people, like younger people, are interested in contemporary music and contemporary sound. They want to know what’s happening now and they’re looking for something with an edge. I’m meeting all these young people that are going back and listening to music of the 60’s. You know like kids running around with Jim Morrison T shirts or Jimi Hendrix shirts. I’m not sure what all that means but I know there’s this idea – a retro movement going on – as we’re coming to the end of the century and the end of a millennium. People are, I think, at that point in time when they are going to want to go back and either hang on to the things from the past -it’s hard to let go- or else they just want to go back and check it out and make sure everything was okay before we let it go.

LS: Well maybe some people are scared of the future.

LE: Yeah, oh I think that’s true too. There’s only scope for solid new expanding music, different sounds, but there’s a lot of resistance too. As you said, because people are afraid of the unknown so there’s resistance to that and what we did with the Freedom Force Ensemble. It showed me that the players, the level of musicianship here in Vancouver, has really grown since the seven years that I’ve been away. These people have really worked hard on their music, on their conceptions, in their lives, and they’ve got a lot to say; there’s a lot more to be said yet. So I hope the community gets out there and supports what they’re doing. It’s difficult for all of us to let people know what’s happening and it seems to be that the big media channels are not really so interested in this information. I mean there is really no notification in the local press, the daily journals or the big radio stations. Maybe just a little bit on the co-operative radio station and a listing in the local free press. With no reviews. Not a single review in any of the local press. And I’m not sure why that is. But I feel like these are things that, if we remain true to our convictions in the music and we keep trying to understand more and more about the things we are ignorant of, we’re going to be building support for this. Obviously this is not music for the masses but I think it’s really important that a few people are continuing this work, continuing this music, continuing this band, continuing this artistic perception.

Originally Published in Coda Magazine, 1990.

Transcription: Gloria Pomeroy, from Kitimat BC. Gloria worked at the BC CAncer Agency. She knew nothing of this music, but after transcribing this interview, she became a listener.