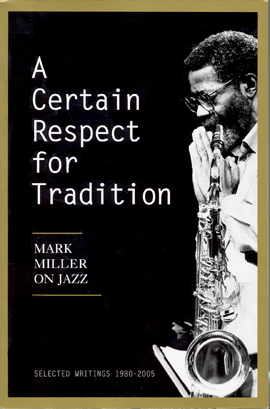

The Mercury Press 2006

©Laurence Svirchev

When Mark Miller quit writing for Canada’s Globe and Mail in 2005, short-form jazz journalism took a major hit. Miller had been at it since 1978, writing more than four thousand pieces in a concentrated, humorous style. His easy-to-grasp, incisive commentary brought both the potential and the already-convinced audience to a heightened understanding of the jazz art form that an army of industry publicists could never hope to achieve.His Toronto central-Canada location was strategically important, because it gave him the opportunity to hear not only the wealth of American musicianship, but also the cream of international musicians who have traditionally have had a hard time accessing the narrowly self-focused market to the south. He had access to that city’s clubs, the splashy atmosphere of the Montréal Jazz Festival, and the startlingly original Festival International de Musique International de Victoriaville (Quebec). On rare occasions theGlobe bought him a ticket to the only major festival in North America that truly presents the breadth of jazz, the Vancouver International Jazz Festival.

When Mark Miller quit writing for Canada’s Globe and Mail in 2005, short-form jazz journalism took a major hit. Miller had been at it since 1978, writing more than four thousand pieces in a concentrated, humorous style. His easy-to-grasp, incisive commentary brought both the potential and the already-convinced audience to a heightened understanding of the jazz art form that an army of industry publicists could never hope to achieve.His Toronto central-Canada location was strategically important, because it gave him the opportunity to hear not only the wealth of American musicianship, but also the cream of international musicians who have traditionally have had a hard time accessing the narrowly self-focused market to the south. He had access to that city’s clubs, the splashy atmosphere of the Montréal Jazz Festival, and the startlingly original Festival International de Musique International de Victoriaville (Quebec). On rare occasions theGlobe bought him a ticket to the only major festival in North America that truly presents the breadth of jazz, the Vancouver International Jazz Festival.

Miller left the newspaper to concentrate on the book-form. Previous to A Certain Respect for Tradition, Miller had already written six books, mainly profiling the history of jazz in Canada, so he was well-situated for this career change. His 2005 book, Some Hustling This, was a uniquely-styled history of how the intrinsically American form of music became internationalized between 1914 and 1929.

A Certain Respect for Tradition represents Miller’s gig-oriented, catholic tastes during his journalism years. Whatever was excellent in the music was fair game for his examination. He had the luxury of newspaper editors who let him run free. Without editorial shackles, he followed his nose through the history of the music, its past, the middle ground that the oldsters grew up with, and the hybrid musics that sprang forth from the genetic variations that jazz inevitably sunders. The book covers a broad range of musicians, like Jabbo Smith, the last of the old-time trumpeters from the beginning of jazz, like the unassailable magicians Cecil Taylor and Steve Lacy, like Canadian Freddie Stone, well-remembered among a certain cadre of musicians.

Miller in real life is a quiet man but his writing kernels pop explosively. He has the gut instinct of a stand-up comedian, making his points in one or two taut lines that typically provoked deeper thought often prefaced with laughter. Here are a few examples:

-During a 1989 Toronto concert, Sarah Vaughan went into a minor on-stage spat when her customary box of Kleenex didn’t make it to the piano. She ended the concert with a Stephen Sondheim composition. Miller’s take: “First it was send out the kleenex, then it was Send in the Clowns.”

-Writing in 1999 about Tony Bennett, “He himself remains in good voice, one part ache, two parts optimism.”

-“Tension is everything and momentum very little, in [Mal] Waldron’s music.” (1985)

-In 1988 he poked fun at Toronto’s notoriously conservative audiences: “[Bobby] McFerrin characteristically leaves his inhibitions in the dressing room. A couple of thousand Torontonians stashed theirs under the seats for most of his one and three-quarter hour concert.”

-In 2001, he had a conversation with the quintessential voice-as-instrument improviser Phil Minton. One of Minton’s monumental recordings was Mouthfuls of Ecstasy, which delved into the words of James Joyce. In bringing Minton to a newspaper audience, most of whom had certainly never heard of him, Miller says, “If Minton has any vocal counterpart at all, it would be Bobby McFerrin. But even that seems a real stretch. Minton’s is far more subversive; it’s a long way from Don’t Worry, Be Happy to Finnegan’s Wake.”

Those sentences are vintage Millerisms and it is no “real stretch” to compare the kind of surprises that Miller dishes up with the contrasts that can be heard in an excellent jazz solo. His writing is rarely judgmental, rather it is illuminatory. With Miller’s observations, a reader can impute more than meets the eye, but never less. And that was what has always been so utterly cool about Mark Miller’s newspaper writing, for the way he synthesized seemingly disparate elements of jazz lore always left the reader with a new insight.

Having said this, let’s get one thing out of the way. Miller had the salient quality of possessing some of the sternest ethics in the jazz journalism scene. Miller has never been a publicity machine for the latest marketing thing. He has consistently bucked the journalistic conservatism that is incapable of engendering the slightest consideration for the newest artistic forms. Miller has always written with tremendous respect about the master innovators of previous decades. But he has also exercised a tolerable gumption when it came to those contemporaries who used the slogan “respect for tradition” to inhibit those creative souls dancing on the edge of a musical abyss.

To the point is Miller’s appreciation of Winton Marsalis, the brilliant trumpeter who has extolled the virtues of the past while castigating the new musics of the present through his omni-present publicity machine. Here is one of Miller’s comments: “His command of the instrument and its effects, both rhythmic and tonal, is effortless, and his improvisations…..have a marvelous sense of authority. While a lesser trumpeter with the same historical pre-occupations might simply sound corny, Marsalis brings to them a certain dignity. That’s enough to carry his agenda forward, but not sufficient to make it completely convincing.” Two sentences of praise, and one remarkably well-aimed torpedo, the most succinct sum-up of contemporary moldy fig-ism that this commentator has read in a decade and a half. A Certain Respect for Tradition, indeed.

He was the best short essay jazz writer in Canada for a quarter of a century, and one would be hard pressed to think of more than four other living jazz writers in the genre as adept as Miller (he’s a very good performance- and off-the-cuff portrait photographer as well). One could only wish that this selection of one-hundred eighty-two essays in A Certain Respect for Tradition could have been doubled to one-tenth of his total output. The hope would be, of course, that Miller has plans for further book releases of his short essays, including his vast number of CD reviews.

Originally published 2006.