Greenwood Press

©Laurence Svirchev

Jazz is a restless music. It grows incessantly through steady maturation but also by unpredictable quantum leaps. New generations of innovators typically acknowledge their roots and artistic influences. Yet the process of discovering new musical possibilities is always accompanied by resistance, and some of the great jazz revolutionaries have been known to make outlandish statements against a new generation of musicians whose only fault was that they heard music in a different way. Louis Armstrong was known to call bebop “Chinese music” (an ironic statement, because classical Chinese music is incredibly complex). There were others who went so far as to say Monk “couldn’t play.” Monk didn’t counter with, “They can’t hear,” but rather with aesthetic self-confidence: “I say play it your own way. Don’t play what the public wants. You play what you want and let the public pick up what you’re doing—even if it takes them 15 or 20 years.”

Jazz is a restless music. It grows incessantly through steady maturation but also by unpredictable quantum leaps. New generations of innovators typically acknowledge their roots and artistic influences. Yet the process of discovering new musical possibilities is always accompanied by resistance, and some of the great jazz revolutionaries have been known to make outlandish statements against a new generation of musicians whose only fault was that they heard music in a different way. Louis Armstrong was known to call bebop “Chinese music” (an ironic statement, because classical Chinese music is incredibly complex). There were others who went so far as to say Monk “couldn’t play.” Monk didn’t counter with, “They can’t hear,” but rather with aesthetic self-confidence: “I say play it your own way. Don’t play what the public wants. You play what you want and let the public pick up what you’re doing—even if it takes them 15 or 20 years.”

Monk’s aphorism brings us to the issue of “free jazz,” “creative music” or similar nomenclatures. Almost a half-century has passed since Cecil Taylor, Sun Ra, George Russell and Ornette Coleman, to name but a few, burst open the floodgates to a broad range of music which is still misunderstood and underappreciated by the majority of American jazz journalists, and of course, the major record labels. The editors, writers, producers and publishers who wish to promulgate these advanced and often exciting musical forms face myriad obstacles by the economics of the music industry. They get stymied by the perception that few wish to listen to adventurous music, that far broader palette of tone, color, harmony and rhythm than the standard approaches of the day. Percussionist and composer Gregg Bendian once told me he unabashedly called it “Weird Music.” The facts, however, speak for themselves. Weird music has been around for a long time now and there are no signs that is going away.

Another strange dynamic in the jazz world stems from a certain American chauvinism. It starts with the fact that jazz originated as an American, and more specifically Afro-American, form of music with roots going back centuries to Africa. Non-American jazz musicians not only have a hard time getting U.S. work visas but they also find it difficult to get enough recognition to be invited to play in the U.S. In the past decade, more and more European improvisers are being reviewed in the jazz press but the annual critics polls reveal that many jazz journalists are unaware of the astounding number of accomplished non-American creative musicians and ensembles.

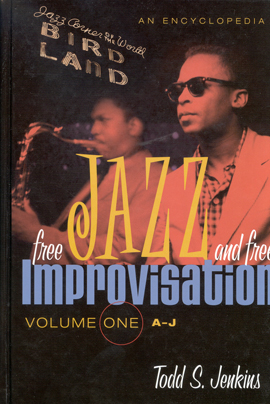

Fifty years into the freedom music phenomenon comes Todd S. Jenkins’ Free Jazz and Free Improvisation: an Encyclopedia , which should go a long way toward giving advanced-thinking critics and academics the ammunition to combat the above-mentioned biases. This encyclopedia does what an encyclopedia should. It opens with an alphabetical list of entries and two essays to give context, and continues with comprehensive A-Z write-ups. The second volume closes out with a useful index and a set of selected readings.

The concise, solidly researched and literate essays are titled “Controlled Chaos: The Nature of Free Music” and “The Path to Freedom.” Even after 15 years of covering the free music scene, often in live contexts involving the cream of European, Canadian and American improvisers, I found that these essays radically enhanced my knowledge of the roots and scope of the music.

Jenkins makes clear that freedom music was as influenced by the social conditions of institutional racism in the U.S. as by the desire of many musicians of different national backgrounds to cross “the police tape of tradition” (which is how Jenkins situates Duke Ellington’s 1947 work The Clothed Woman). Equally, Jenkins makes clear that many of the early free musicians started out with R&B, swing, church and bebop backgrounds, i.e., traditional black American music. One exception was Steve Lacy, who began his career even further back in the Dixieland style. In addition, all generations of freedom musicians have been strongly influenced by modern classical composers such as Schoenberg, Varèse, Cage, Feldman, Stockhausen.

Jazz has always held a fascination for European audiences and musicians. But by the 1960s Europe’s creative musicians began selectively to drop their adopted American conceptions, refurbishing their music not only with spontaneous composition but also traditional European folk melodies. British musicians rapidly conjoined with South African musicians like Louis Moholo to create hybrid musics, consciously defying the reign of apartheid. From Norway to Spain, freedom music began to traverse the continent. Even in the Soviet Union and the dominated Eastern European countries, musicians were sounding the chimes of freedom flashing. What had started as an African-American music now became an international and polymorphic music. The only ones who didn’t know it, and still don’t know it, are those who seem incapable of looking beyond the borders of the country of free music’s origin.

Jenkins’ chronology starts in 1949 with Lennie Tristano’s recording “Intuition” and “Digression.” It then jumps to 1955, telling the reader that “Albert Ayler meets Charlie Parker in person, Steve Lacy joins the Cecil Taylor Quartet.” To emphasize the giant-to-giant lineage, 1955 was also the year Hamid Drake and Gerry Hemingway were born. The chronology ends in 2003, with the kind of bad news that so often plagues free music: “The city of Berlin [Germany] announces it is canceling supporting funds for the Total Music Meeting.” Fortunately, The TMM continued, holding its latest edition in 2006.

The bulk of the encyclopedia is taken up by the alphabetical listings. As history would have it, major-league players are the first and last entries: AACM & Zorn. The in-between is chock full of Ty Cobbs and Babe Ruths. Cecil Taylor gets 14 pages, British saxophonist Evan Parker gets three and Albert Ayler gets nine. The greatest of modern clarinetists, John Carter, only gets half a page, perhaps in line with his largely out-of-print discography.

The major-league players not only get their biographies and important recordings documented, but their musical contributions are informatively discussed and more importantly, accurately assessed. Here is how Jenkins sums up Cecil Taylor: “The combining of classicism, jazz traditionalism, and his own unique conceptions has made Taylor’s body of work matchless and seriously controversial…. Taylor has been so far ahead of his time for so long, the rest of the world has yet to catch up to him.”

Jenkins covers the disparities of geography, time and musical approach quite well. Barry Guy (Britain), Wadada Smith, Butch Morris and George Lewis all get their individual citations, but they are also cited as guest conductors with Vancouver’s NOW Orchestra, a stellar large improvising ensemble constantly working since 1977. Although relatively isolated by geography from the rest of North America, Vancouver (my home city), like London and Amsterdam, has boasted a creative music scene for over two decades. Jenkins insightfully includes the Vancouverites François Houle, Peggy Lee and Dylan van der Schyff, all younger players with outstanding international collaborations to their credit.

To back up his research, Jenkins also includes a list of suggested readings from the likes of scholarly jazz writers such as Whitney Balliett, A.B Spellman and Martin Williams. But the first book I went looking for is a sine qua non of improvised music, British improviser Derek Bailey’s Improvisation: Its Nature and Practice in Music. This book was indeed listed.

Two periodicals, Cadence and Signal to Noise, are noted, but Coda is not there. This may be the only omission of consequence, for Coda was dedicated since its founding in 1958 to international improvised music. Coda was typically the magazine that brought new improvisers to the attention of producers, listeners and critics long before the glossy jazz magazines did. Not only that, butCoda also gave a first by-line to many who would later become well-known jazz writers. A reference to the historic Coda would have been of supreme value to future writers and researchers.

Via an Internet discussion, Mr. Jenkins volunteered that in the final proofing of this eight-year project, the reference to Coda was inadvertently dropped. I take that as a sign that editors and writers need to be extra vigilant when it comes to critically important references. That said, missing a few names or references is no tragedy. Free Jazz and Free Improvisation is not only seminal, but verges on being completist. This is the only serious encyclopedic work on jazz and free improvisation to date in English, and perhaps in any language. Music libraries would be making a sad mistake to leave it unordered. It should be treated as a standard reference text for the genre. It provides the basic biographical information, historical contexts and chronology for curious listeners, music journalists and academics to understand a most profound artistic revolution. Such movements typically burn themselves out and turn into their opposite, but the free improvisation movement continues today, perhaps as in the title of the Albert Ayler composition, “The Truth Is Marching In.”

Originally published in a modified form in Jazz Notes, the house organ of the Jazz Journalists Association, 2005